A conversation with Megha Malhotra

How does peace work? Let us hear that first hand from Seagull Foundation for the Arts’s PeaceWorks team: “Yes. Certainly more than, say, war, conflict, violence, destruction. Think about it. See the world around you. On your TV and your laptop and your mobile. The more the news hits you, the more numb and disinterested you get. After all, you say, how much can you take? At Seagull, we decided to do something about it. We chose the arts as our ‘tool’ of communication. The core idea being: hey, we need to live with difference and allow it the same space to breathe that we, us, ourselves demand. That’s it.”

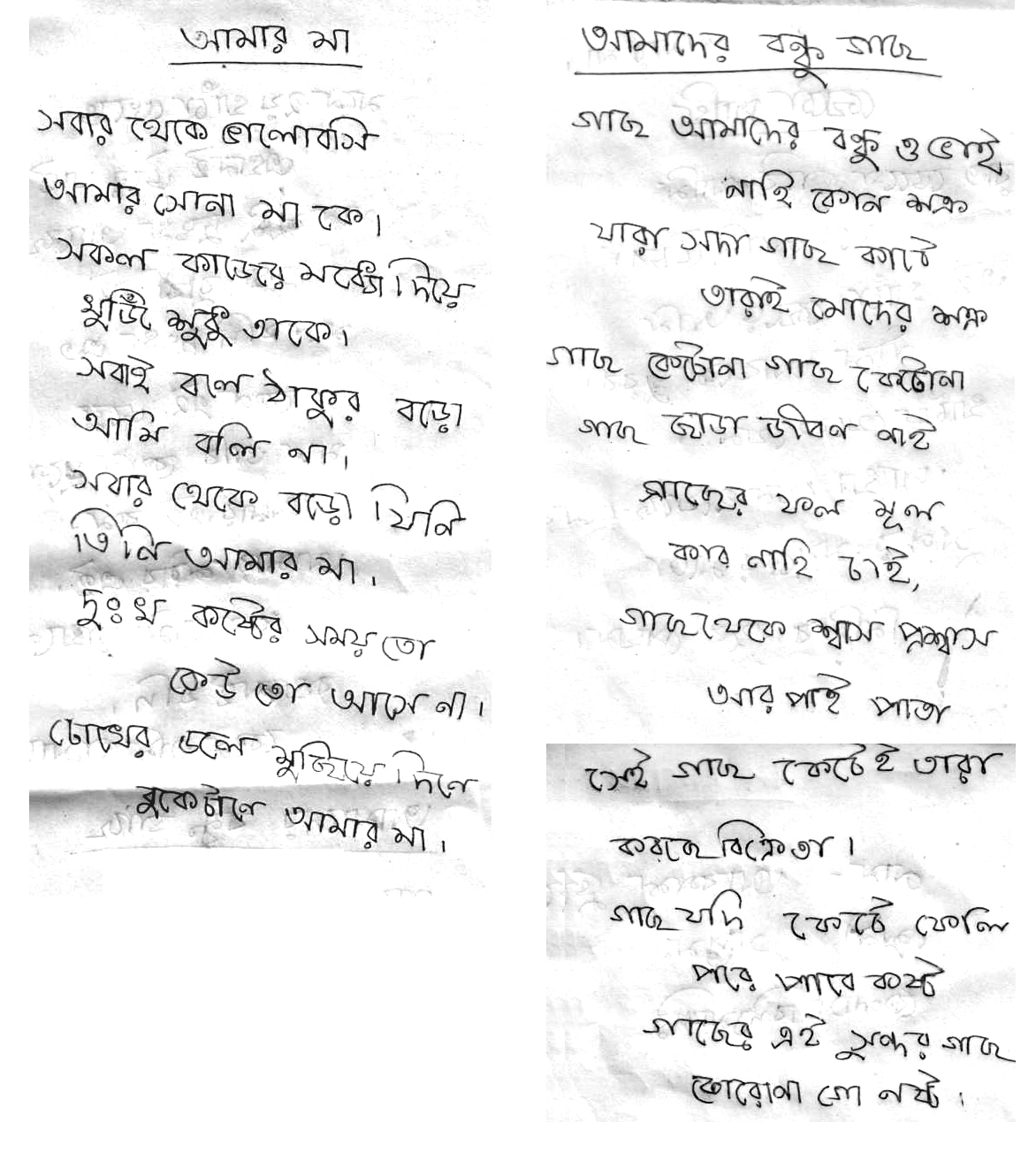

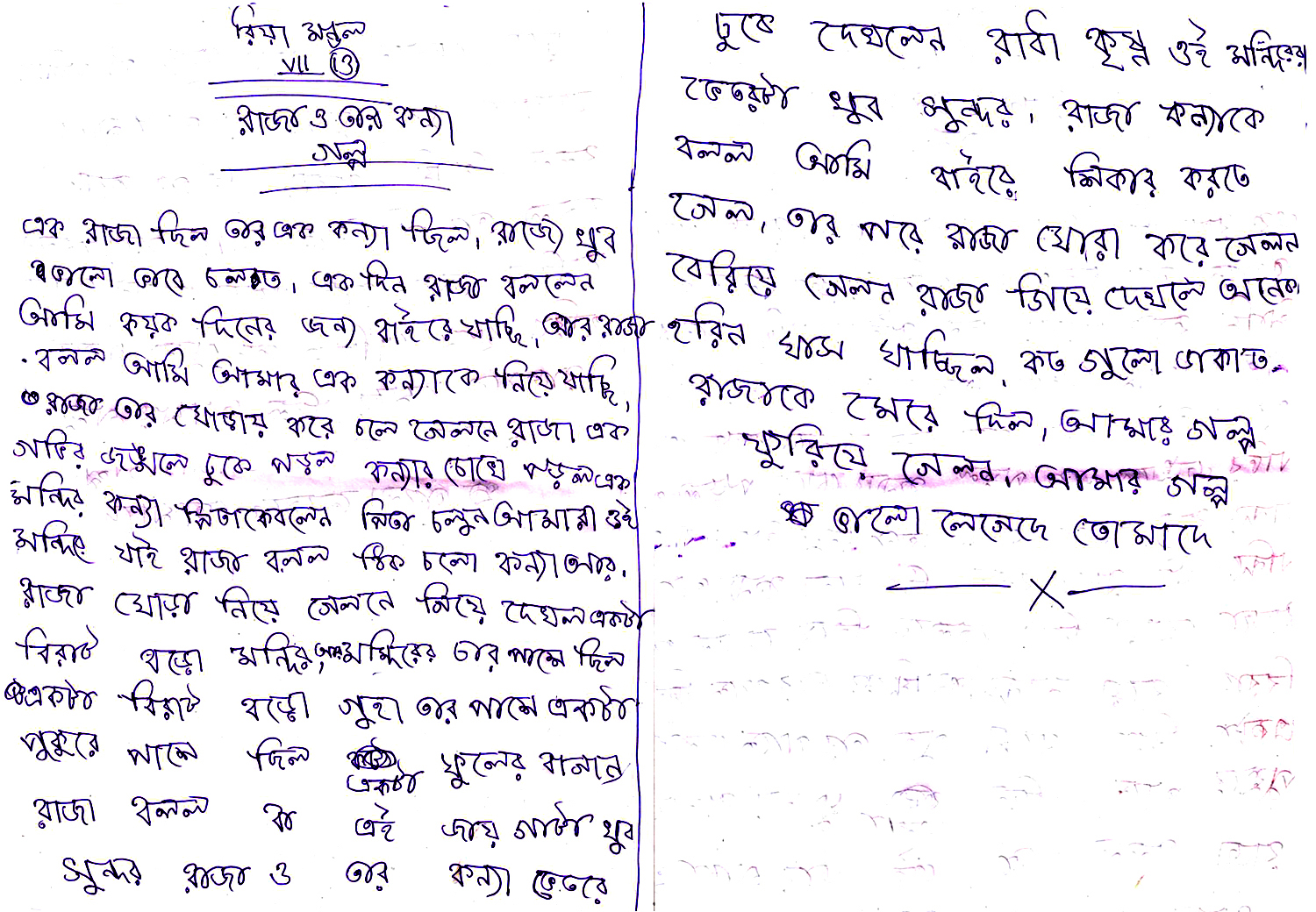

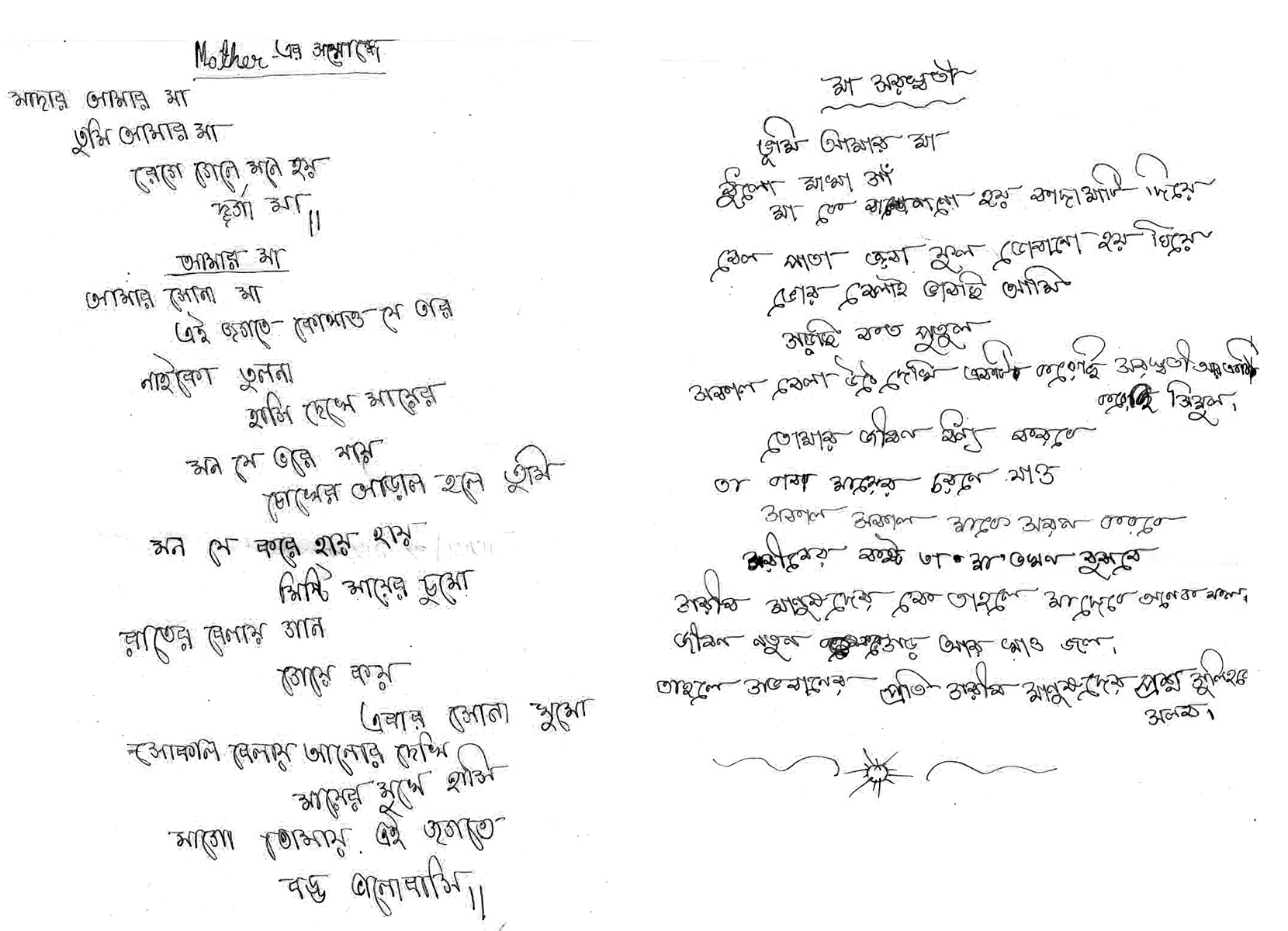

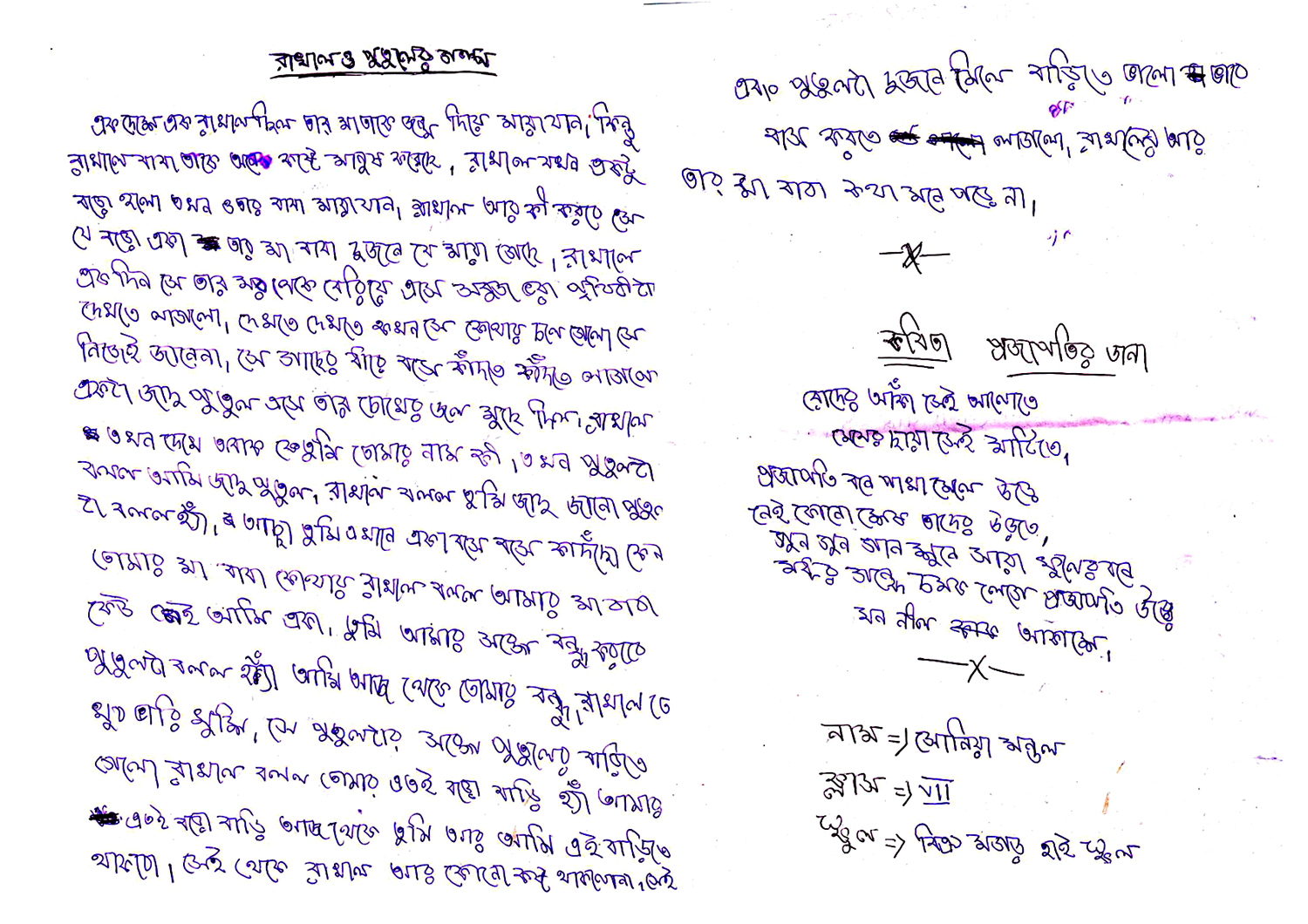

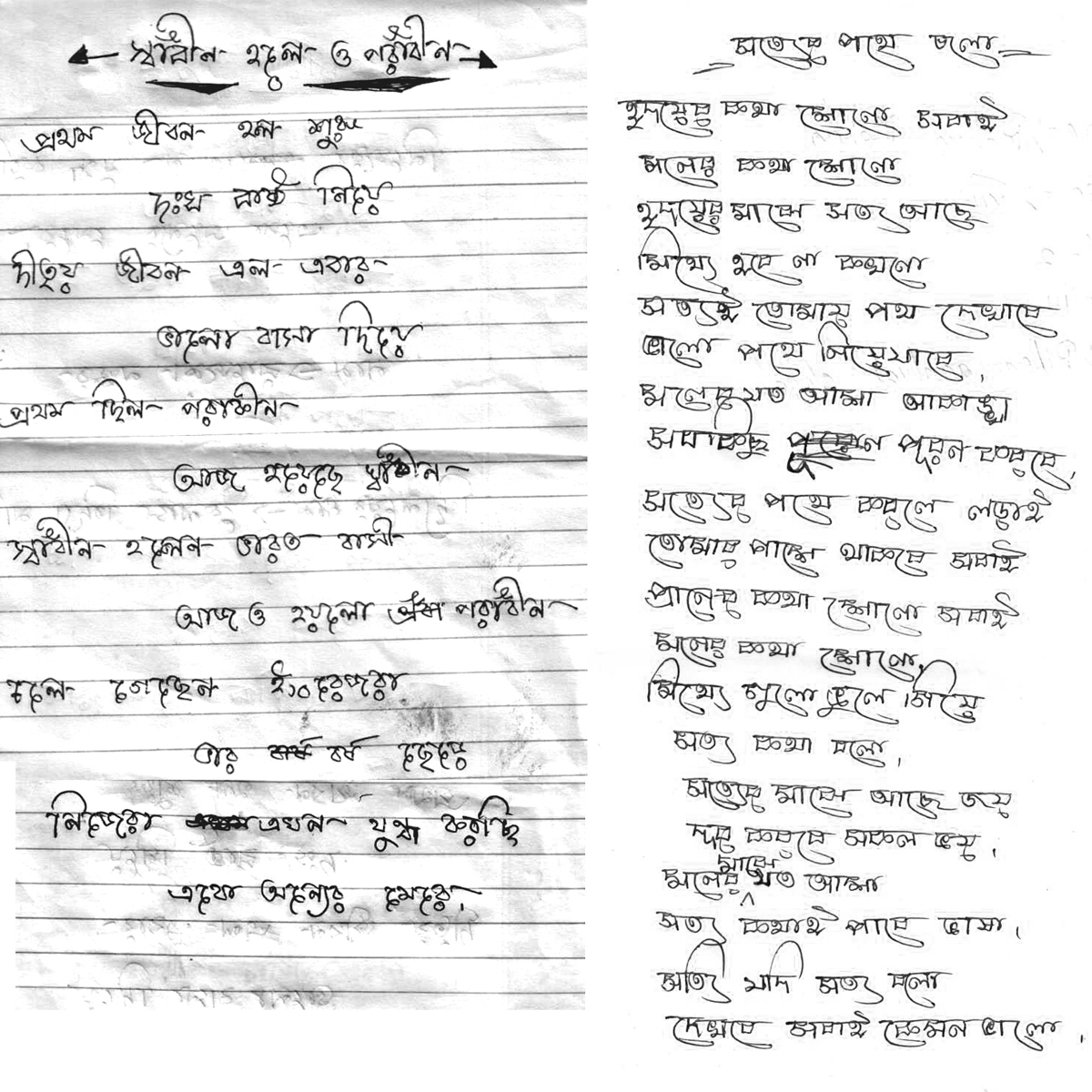

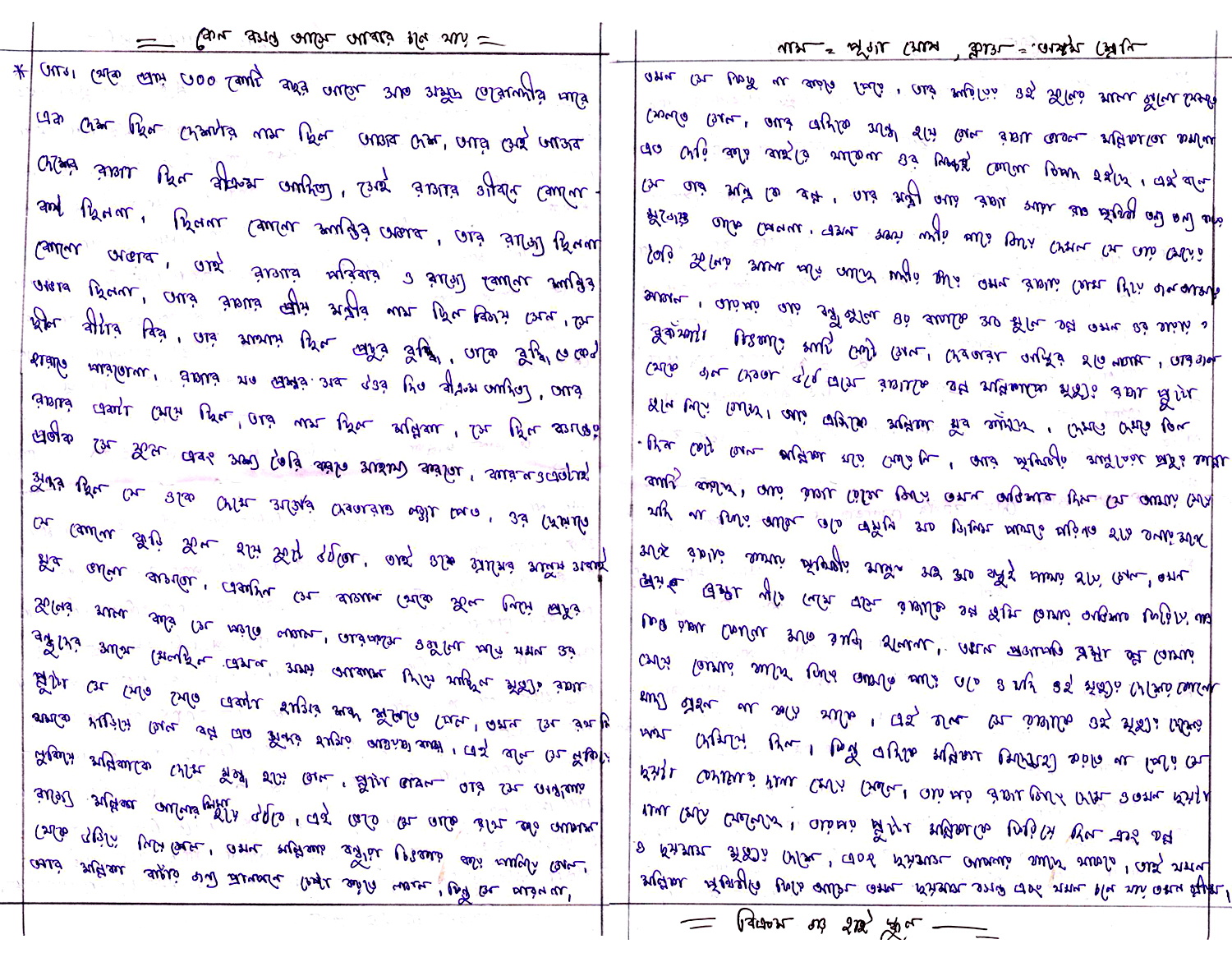

We at Aainanagar are honoured to have a large collection of artistic and literary contributions from the children participants of PeaceWorks. Their little pieces, which we have consciously pasted in between the dialogues here, intercept and distract this interview but at the same time (at least to us) add an important context to it. Megha Malhotra, on behalf of the project, tells us how peace may really work in changing the world, as against many of our beliefs. Through her thoughts, initiatives and extensive work in dealing with violence, peace and childhood, Megha gives us a rare glimpse into a whole new way of life.

Q. How long have you been working on PeaceWorks?

Megha: I have been in charge of the project since 2008. When the project was launched in 2003 I was running the Seagull Bookstore. So at that point my involvement with PeaceWorks was in terms of the Seagull website – since I am responsible for the design and maintenance of the website since 2000. At Seagull we are a small tightly knit group. Each one of us has her primary responsibilities, but we also pitch in wherever required, as and when required. So there has been a tertiary involvement right from the beginning, but yes 2008 was when it became the main focus for me.

Q. What were your

- a) inspirations (similar projects, experience etc.),

- b) professional training regarding working with children?

Megha: I have no professional training regarding children. I went to art college to become a graphic designer and subsequently for the longest time ran a design studio. The only training in relation to children comes from the life experience of having raised two of mine.

Q. Tell us a bit more about the PeaceWorks project from the beginning. How many schools/children did you start working with? Who else were involved in it – administrators, volunteers? What were the initial projects?

Megha: The horific events that followed the Godhra train burning incident was the impetus for the PeaceWorks project. Setting up the project was a very personal response of our Managing Trustee Naveen Kishore out of a deeply felt need to work with young minds, using the arts to foster a spirit of equality, peaceful coexistence and mutual respect and sensitivity across differences. PeaceWorks is a people’s movement of transformation, reinvention and restructuring of social consciousness.

Over the years, PeaceWorks has worked with scores of students, teachers and parents across the country and in Pakistan. We have taken our Dialogue for Peace project to Kashmir and now have international partners as well.

PeaceWorks started with taking films to schools and holding post-screening discussions. The idea was to create a platform that allowed questioning and challenging preconceived notions. From films we progressed towards conducting workshops, discussions and debates for a deeper engagement with the very idea of ‘peace’ and what it means to all of us— understanding conflict and identity.

The core team then comprised of Managing Trustee Naveen Kishore, trustees Anjum Katyal and late Dr Somnath Zutshi along with other colleagues. Apart from the core team, several renowned arts practitioners and academicians were involved in the project— conducting workshops, participating in discussions, seminars and interacting with students and teachers. To name a few, Anand Patwardhan, Jayant Kripalani, Jan Natya Manch, Probir Guha, Sumit Roy, Sister Cyril, Prof Minu Tharoor, Aijaz Ahmed, Lalit Vachani, Amit Chaudhuri, Manjula Padmanabhan, Dilip Simeon— the list is not exhaustive and I cannot possibly add all here, unfortunately.

Q. Raising the funds – was it a smooth or a difficult process?

Megha: Seagull has been supported by the Ford Foundation from 1987 to 2009. When the project was launched Ford Foundation was convinced about the need for this work. However since the support ended in 2009 (Ford Foundation’s focus area shifted from the arts to Women and Reproductive Health) it has been very very difficult in terms of raising funds. Primarily I think because the work we do is extremely long term and intangible. And funders today are increasingly only stressing on quantification and statistics. What I mean is, I can give you the number of students/teachers we worked with in a financial year, but how do I measure the intellectual and emotional impact our work has had on them in that particular year!

Q. This is a question that we, from Aainanagar, have been trying to understand through our work for a long time. It would really be great to have your input since you have been doing such an important work in this field. So, here goes: What is your personal definition/understanding of ‘violence’ as an act and as an experience – in general as well as with respect to a child’s mind?

Megha: This is a rather difficult question that could have several answers! But to put it in the most concise manner I would say any act physical or emotional that compromises an individual dignity and violates his/her basic human right is violence.

Q. Narrowing down our previous question – what is your experience/opinion regarding how children deal with ‘violence’ in their creative expressions, for example story-writing and drawing pictures? In our experience, stories for children (say, for example Grimm’s fairy tales) as well as stories written by children (for example Rohan’s story for Aainanagar) does contain a lot of violence. Do you consider that to be an inevitability or something that can/should be avoided eventually? Basically what we are asking is, what is your personal feeling about the intrinsic violence in a child’s creative mind?

Megha: The world as it is today has made exposure to violence ‘inevitable’ across continents/societies/class/creed. Some of us experience violence in the personal sphere and others are forced to make it a part of their daily diet through the onslaught of the visual media. So much so that I am not sure we are even thinking about it anymore. It’s just there. It is inevitable for a child to be exposed to all forms of violence from a very early age.

Its hard to avoid it hence it is imperative for our young to understand right from wrong. Creative expression is a very powerful tool in achieving this understanding. And that is an important thread in all our work at PeaceWorks— to ‘see’ in a manner that leads to questioning, analyzing and inspiring action against all that is wrong. Of course we may say ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ are relative terms. However there are some ‘wrongs’ that are universally unacceptable and non-negotiable.

Q. The process incorporated in the PeaceWorks story-writing and story-telling sessions – is there a conscious effort of connecting the child’s personal experiences and the art that s/he creates? If yes, then how? If not, then why?

Megha: Interaction forms the backbone of our story writing/telling sessions. So the child’s personal experiences naturally do come into play. However, we prefer it to be an organic process and encourage our volunteers and resource people to allow it to come naturally.

Q. How do children that you have worked with react to the ‘non-physical violence’ of everyday life? For example we have seen children in the last ‘Golpo Mela’ organised by PeaceWorks reciting Tagore’s poem ‘Pujar Saaj’ which is a story of greed and poverty as well as something much deeper regarding the ‘virtue’ of ‘accepting one’s fate of poverty’ as against ‘raging against it’… When you work with such texts for children, do you allow the politics of violence inherent to those texts in many levels to be discussed? Why?

Megha: How the politics of violence inherent in texts is dealt is absolutely connected to the dynamics between the storytellers—in this case our volunteers—and the audience. Their age, their level of understanding. What we do attempt consciously is to encourage discussions that highlight the fact that there is no single reality, nothing is sacrosanct.

There are multiple perspectives that need to be understood.

‘Learning to live with Difference’: the PeaceWorks philosophy is not just about religious difference, cultural difference or socio-economic differences. It is also equally about intellectual and philosophical differences.

Q. Tell us a bit about the Share Stories Open Minds project. What is your own definition of ‘stories’ and what kind of stories would you consider to be working towards opening the listener’s mind and in what way?

Megha: Storytelling is one of humanity’s oldest art forms and an enduring educational method. Stories can spark social changes. Since ancient times, ideas and values embedded in stories have educated, inspired and motivated listeners.

This is what Share Stories Open Minds aims to do for street and slum children, who do not get the exposure and opportunities that are so taken for granted for children from privileged backgrounds. Exposed to crime, violence, abuse, these children are struggling for basic amenities. The state is facilitating basic education, however it takes so much more than a basic education to make a responsible evolved citizen. This is where our storytelling project comes in. Volunteer-based so far, this initiative sparks the imagination and plants important ideas through fun and games and the powerful world of stories.

Our volunteers are a wonderfully diverse group of people, bringing a tremendous amount of insight to the project, not just by reading or telling stories but also bringing valuable life-experiences into their work.

We made a small beginning by launching the project in five centers in Kolkata: Disha Foundation, Child Care, Kalighat Police Station, Bhawanipore Police Station and Beniapukur Police Station. Currently we are working in nine centers and we hope to add many more by the end of 2015.

My own definition of ‘stories’ is ‘life-experience’— I believe all fictional accounts too have ‘life experience’ as their backbone.

Q. Tell us a bit about the Anne Frank project. How did it develop? Why is it called so? Are children encouraged to keep a diary as part of this project? Do you feel it is important for a child to keep a diary? Why?

Megha: Anne Frank- A History for Today is a project that originated at the Anne Frank House Museum in Amsterdam to spread the message of Anne Frank’s life and ideals throughout the world. It consists of an exhibition on Anne’s life curated from archival photographs from the museum’s collections. This exhibition has travelled to over 60 countries worldwide. Anne Frank House also develops educational material around the Anne Frank story.

I came in contact with them at a conference for history teachers in Turkey mid 2012 and suggested a partnership for India. Much to our delight the idea was welcomed by the Anne Frank House with open arms and November 2013 we launched the project in Kolkata with the travelling exhibition, film-making and teacher training workshops. Subsequently we also developed a Human Rights Supplementary curriculum with the Holocaust and the Anne frank story as the backdrop.

The exhibition has travelled to several schools in Kolkata and is now being shown in Bangalore.

Some children are naturally inspired, after viewing the exhibition, to keep a diary and I do think it is a powerful means of expression. It is very important for children to have the ability to express. The means of expression— whether it is a diary or through art or drama or storytelling— needs to be their choice.

Q. The Art that the children involved in these projects are coming up with – do you have any plans for these being exhibited for a larger public or/and putting them up for sale – as many organizations and NGOs do?

Megha: We have been exhibiting the children’s artwork every year at Golpo Mela, where we get a fair amount of footfall. However, we do not plan to put them up for sale.

Q. Talking about a larger public – what have been the reactions of the schools (by that we mean the must-have-been-different reactions of the children, the teachers, the parents and the school-authorities) that you have worked/tried to work with? We remember from when we met for the first time, you mentioned that many of the popular schools were not very interested with this project to begin with… Basically, what have been the trend of acceptance of and involvement in PeaceWorks among its subjects and its audience?

Megha: Across the board we have found great excitement and encouragement with the ‘idea’ of PeaceWorks. We are constantly told how important this work is. But unfortunately in practice the response could be far better. We find a lot of schools and teachers do not actually actively get involved due to ‘lack of time’ and ‘syllabus pressure’.

Q. How has it been working with children from different socio-financial backgrounds? As far as we understand – PeaceWorks is about working with a larger miscellaneous group while Nabadisha is restricted to street children… Tell us a bit more about both.

Megha: PeaceWorks has been working with a large cross section of children from various socio economic backgrounds for many years. While the Share Stories Open Minds and the Arts Education project are for children who come from largely underprivileged backgrounds, we do have other projects, such as Teaching Divided Histories, the Anne Frank project (under the larger Human Rights Defenders program), Dialogue for Peace: the Kashmir project and the Exchange for Change project (in collaboration with the Citizen’s Archive of Pakistan) where we work with children from the so-called privileged background. This has actually been a conscious decision.

The Nabadisha program was launched by the Kolkata police with the main objective of keeping children off the streets. The police provide a classroom space for these children, and various NGOs conduct classes there. These classes are mostly with the purpose of helping the children out with homework etc. What PeaceWorks does is provide the co-curricular activities through the Share Stories Open Minds and the Arts education program. We collaborate with the Kolkata police in five of their Nabadisha centres, with NGOs in four centers and also work in three government schools, both of which fall under the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan scheme.

However these are not mutually exclusive from each other. Most of our projects bring children from diverse backgrounds together. The idea is to provide a ‘lived’ experience of ‘difference’ For example every year at Golpo Mela— the PeaceWorks Storytelling Festival, Nabadisha children come together with children from private schools and celebrate Children’s Day together.

Q. What has been the most successful project organised by PeaceWorks so far, in your opinion? In what way?

Megha: Gosh! Impossible to answer. All the projects have seen varying degrees of success and each one of them leaves us with the thought— ‘the work has just begun’.

Q. This is related to a previous question… What do you think are the effects of ‘stories’ on the adults? Do you have any plans for opening up PeaceWorks for the adults too?

Megha: I am assuming you are referring to the volunteers when you say effects of ‘stories’ on adults. I am convinced it’s a huge learning process for them too. In the telling of the stories and the interactions and discussion I think the children are teaching as much, if not more, to the volunteers.

Adults are very much a part of the project already— teachers that we work with— and our volunteers.

Q. What are your plans regarding taking PeaceWorks forward?

Megha: Immediate plans include scaling up of all the current projects. We plan to also increase the reach of the project beyond the country and develop projects that involve students and teachers from the sub-continent.

************************************************************************************

Finally, few words from those who make peace work:

“We work with a group of very young children from the NGO Hamari Muskan. We conduct storytelling sessions for them at St Josephs College, which is in North Kolkata. The sessions take place every Saturday afternoon from 3-4pm. The children are always very excited about any new activities we have for the day.

With each activity we try and instil values into them. Our focus is also towards helping them to communicate in English. We make it a point to use common English words in the narration of the story, so that the children can start using those in conversation. Apart from this, there are other activities like drama, dancing and outdoor games, breaking away from the conventional method of indoor education.

With the focus on the overall development of the child, we look forward to spending more time with the children and sharing our experiences as we go along the journey.”

– Divya Malani, Shelly Kothari, Volunteers

***

“On the day I first walked into Bikramgarh Girl’s High School, I was faced with the daunting prospect of appealing to ninety girls, ranging between the ages of four and seventeen, who automatically resented me for waking them up from their afternoon siesta. Aliya, my fellow volunteer, and I decided to focus on a small straggle of sleepy heads who were to perform at the upcoming Golpo Mela. We took them to one end of the huge hall room where the girls sleep and began to practice the play they intended to perform. The first half hour it was just the two of us struggling to infuse our enthusiasm into the reluctant performers. Then something happened – a catcall from one of the girls led to a comment from another and suddenly we had a very active audience with opinions on every throw of dialogue. The play turned out to be mighty fine and everyone thoroughly enjoyed themselves. There also emerged raised confidence levels, a couple of talented actors and show of leadership skills among some of the girls.

That was two years ago. When I walk in now, I am greeted by an excited bunch of young people who jump up at the prospect of the storytelling session. A couple of weeks ago I declared that the next session I would be part of the audience and it would be the girls who would take up the part of storyteller. When I went in for that session, I had expected that there would be one, perhaps two stories that had been prepared and that the authors would require a lot of coaxing to step up and read out their work. At the end of the interactive games for the day, (a relatively new practice which is carried out by the brilliant Yash Jalan intended to ensure that the girls continue to have contact with sports at least once a week), when I asked for stories, the girls rushed back to their dormitory to get their notebooks and I was dragged to the roof. The stage was set in the form of the author’s chair, the only seat from which the author would be allowed to read their work. The stories poured out, one after the other – fairy tales, rhymes, short stories, they had them all. Everyone wanted a chance to tell their story and there was very little coaxing that had to be done to get the most reticent of them to perfom. There were so many that I failed to give everyone a chance despite extending the session for another 30 minutes.

In two years, these girls have blossomed from shy, scared youngsters reluctant to share their thoughts to individuals brimming with confidence and belief in themselves. All of this, they assure me, is because of our story telling sessions“

– Anushka Halder, Volunteer

***

“I am very pleased to be associated with this project (Arts Education). I am feeling a change inside me along with the children. The work that I have done in the last phase acted like an ice breaker for both me and the children. It was like forming a bond from within-raising a platform from where we can start working on a deeper level.

In the coming months, I will develop improvised fragments of different structural theater pieces and gradually try to chain them into a performance, improvising the pieces along with the children.“

– Arpita Guha Barman, Alternative Living Theater

************************************************************************************

Artistic and Literary contributors: Suman Purkait, Sonia Mondol, Ajoy Rajbanshi, Debnath Mondal, Deepa, Jyoti Rajbanshi, Kundan Ray, Lakshmi Mondol, Md. Afrid, Piyali Nayak, Rahul Rajwanshi, Rana Deashi, Saba Parveen, Shama Parveen, Sony Sharma and many others.

We are indebted to Paroma Sengupta for keeping in touch with us on behalf of Seagull and PeaceWorks. – Aainanagar

1 thought on “How Does Peace Work?”