Sagorika Singha

Sagorika Singha is an ardent lover of stories of all forms – cinema, books and life. At other times, she is a research scholar in cinema studies.

Most everything you think you know about me is nothing more than memories.

— Haruki Murakami, A Wild Sheep Chase

*

Drifting clouds. Tadpoles in the pond. Chasing butterflies, grasshoppers and dragonflies. The fragrance of petrichor. Being surrounded by the innate madness in general banality. Few ephemeral pleasures seemed so much more in my childhood when reflected back upon now, years later. Memories coated with patina magnify and metamorphose certain incidents and people and end up as a strange concoction or perhaps. In my ordinary childhood I managed to find happiness from unexpected quarters and objects. I was delighted by the objects and people around me, charmed by the green pond in the backyard, enlightened by the luminous moonlight, engulfed by self indulgence as in giving myself to brooding – fleeting but lasting pleasures they were. I believe I was precocious in understanding the world around me, at least the natural world or whatever you would like to think of when I say natural world.

It is maddening and chaotic to rummage into the memory vault and slide your fingers into the sack full of long-lost remembrances, mementoes, incidents, people and other paraphernalia to draw them out in order to give them a new life, a new version with its own reality.

In attempting to do that I ended up in that corner of my cobweb-ridden memory recollecting one of the oldest ones, and in its resurrection realised that perhaps I can never recreate it the way it was the first time.

2010s.

Aare Raja babu, aiyo tara tari aiyo babu re babu!1

The remoteness I had drawn between my childhood fascinations and the drudgery of a grown up existence took a beating when a proposal for an anthology came which tried to collect the varied memories of people from the valley – of the people and things and events that they hold dear, that shaped them the way they were, that helped them to understand life, that made their life experiences richer. When given the opportunity to write I was asked if I remembered the belunwalla2.

Could I be able to write my memories of him and in some way also incorporate other people’s memories of him? I was thinking at that time that this is it. Some things occur in a full circle. The memories you believed you left behind chase you unconsciously and ensure a place, a memento that will not let you forego it so easily. It is then that I set out to explore the man behind my memories and in spite of some initial hiccups I unfurled my expedition in trying to enter other people’s memories of that ageless man that Raja Babu was.

It has less to do with the person, rather it is the memory of him that induces something else, something we cannot so properly define – an instance of happiness, a moment when ignorance was liberating, a leap in time to a period that we know we have lost forever in chasing more meaningful ambitions. It comes as a zephyr, momentarily overwhelming us with images of a technicolour past before carrying away our innocence little by little in its wake. Raja Babu, Belunwalla, Daat Bhanga Bura3 or Laxmi Debnath no matter by which name you call him – he acts as the harbinger of those times, he is the ticket to our forgotten moments in the past and helps us steer towards inaccessible territories which have disappeared from the map of our memories forever.

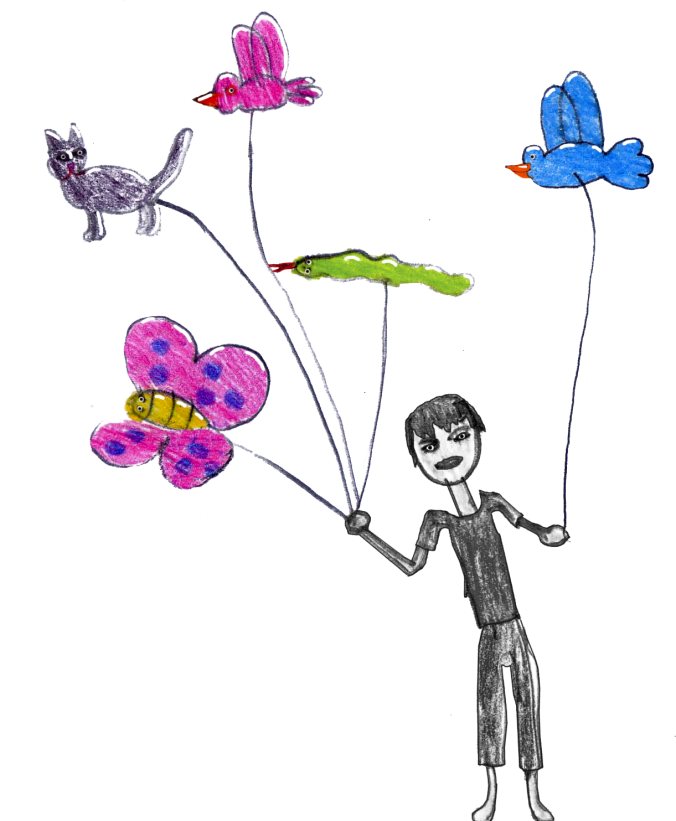

It seems the belunwalla was active from 1980 to 2009. He appears to be clearly etched into the recollections of those born in the 1980s. In a random search for the belunwalla in the Internet, I was surprised, not of the reminiscences but that the memorialisation was spread across the world of the Internet as well. People in their late 30s in local forums mused and recalled their memorial mementoes with objects (such as line buses, ringdom molom) and people that they could no longer access. While going through quite a number of such forums, I repeatedly stumbled across the ruminations about the whimsical belunwalla and the attempts to recreate his expressions or remember his antics – his catch phrase Aare Baap re Baap, the tunes he whistled. A YouTube video that appeared like a teaser trailer to a proposed documentary was littered with comments from numerous users4. The common strain to all of their voices was the sense of acute nostalgia and loss. Most of those participating in these forums were in their mid 20s to late 30s. The reason behind the nostalgia tinge was the snapshots that the compiler of the video had managed to place. They also were able to record the voice of Raja Babu which was used for the trailer. The still images used were very sepia toned and very characteristic of our recollections of him. One aged man with numerous balloon-crafts flanked by children between the ages of 5 and 11 who were enthralled by the strange man with faraway tales. The uploaders of the video had named the ageless man ‘Mythical Bird’ – an apt epithet. A myth he has been but more consuming is the fact that his ambiguity mattered less and less, how it was the complete ignorance of his past that morphed his image to us as children. The fact is that even though he evokes heightened nostalgia we actually do not know him as a person, his personal history, his reason for choosing his vocation. He is only a stranger after all, a beloved stranger nevertheless. It is the way we remember him that enables us to talk about him, draw his picture for posterity, transform him into a myth, a folk hero. He is a myth. Does he exist? That his mysteries heightened our imaginations more reveals the sort of pleasures we derived from knowing less as a child and being enamoured by the unknowingness of things and people.

1990s.

Bhuban paharer moyna kotha je koy na…5

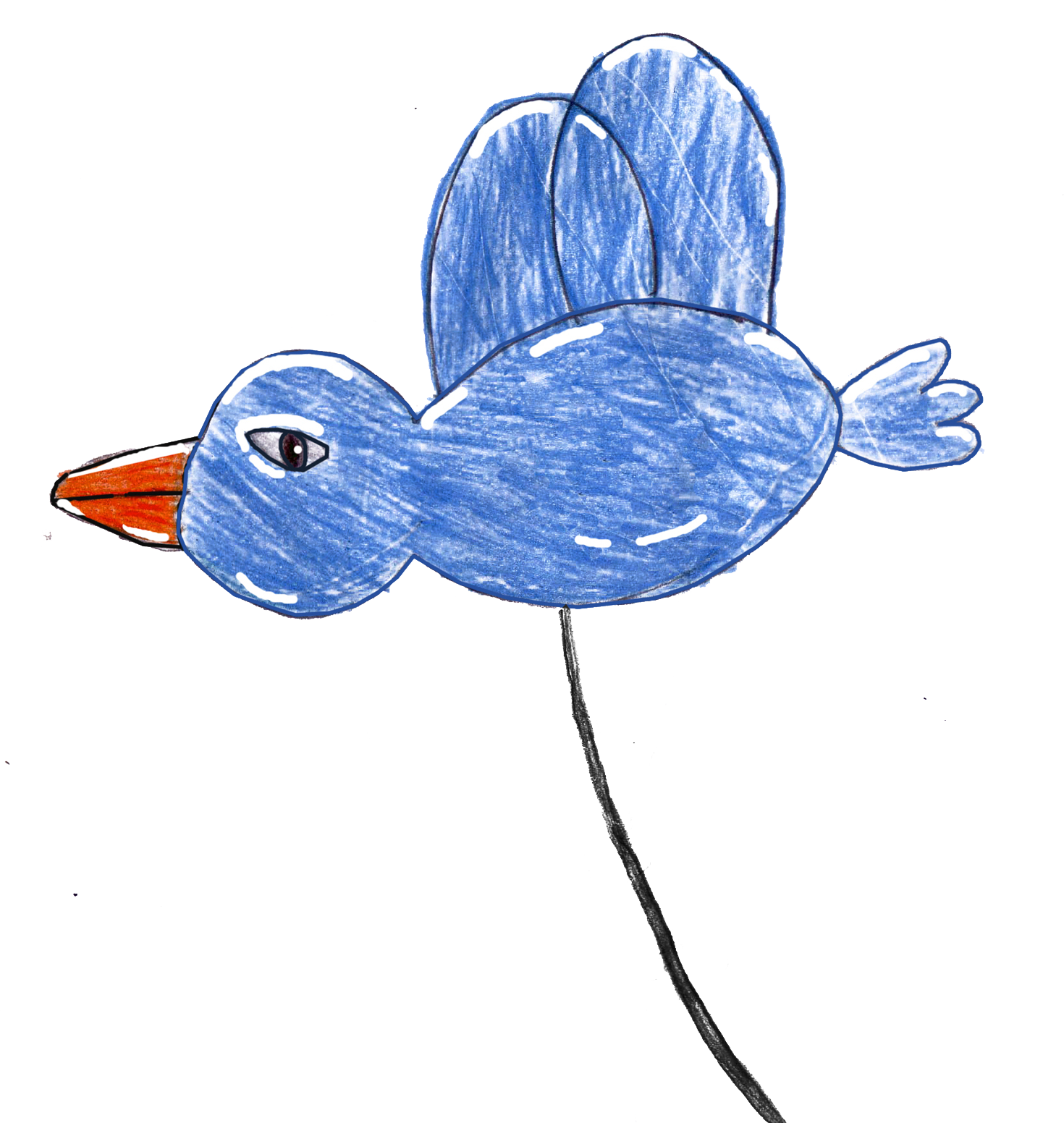

It was an ordinary day, sunny and pleasant. I was 8, alone with my mashi6 and my younger sister embroiled in our regular afternoon routine. Looking at the sun rays through squinted eyes waiting for some kind of marvel to occur, I was in my green courtyard with the mighty coconut tree in the middle and surrounded by the mango trees, when some colourful balloons swirling over the bamboo beda7 caught my eyes. Initial glee gave way to curiosity, a strange previously unheard whistle followed. Running towards the front gate I was startled to find an almost wizened old man, with numerous balloons shaped in a variety of animals and birds, looking straight at me. The initial dread gradually turned into a smile when he handed me a bird- shaped balloon while uttering in a sing-along tone, “Bhuban paharer moyna kotha je koy na…”

Even though my otherwise uneventful childhood was strewn throughout with moments random and unaccounted for that somehow stayed, it fills me with acute nostalgia and melancholy to think about that particular bright sunny day and the even brighter patch left by one stranger in the life of a wild-eyed child who was more engrossed in making her dull routine a fancy one with her teething younger sister in tow. That strange, sing-song man no longer felt a stranger. As children we were told to be wary of people we were unfamiliar with but we always had machinations to navigate our fears. The horrid tales of the legendary Kuchidhora8 was perfect material for Sunday afternoon storytelling sessions, for some delightful and frightful situations that led up to us being cosy with our mothers – the narrators of these tales.

Since that day me and my younger sister would eagerly await the belunwalla’s visit for a break in our banausic day, to buy his transient iridescent wares but more so for his strange locutions that meant nothing and still evoked a warm rejoice. The man from Bhubon pahar or so we assumed in connection to his frequent reference to this strange faraway abode in the hills, kept on paying his infrequent and sudden visits, becoming more familiar with us and we with him. His quirky expressions and his whistles became something to reckon with. The former dread was taken over by an odd familiarity that made us beckon him with unpretentious glee whenever we happened to see him.

I always presumed that our Raja Babu, one of his many popular pseudonyms with which I became familiar only later, travelled with his wares only in my part of the town, his demesne. His old demeanour and natural desultoriness perhaps blinded my opinion. However, as I was to discover many years later, the man from Bhubon Pahar was not so esoteric. He travelled throughout the length and breadth of the valley – from Kalain to Meherpur, from Sonai to Ramnagar, and was equally popular in Karimganj as well. His mesmeric whistles and vibrant balloons shaped in the form of monkeys and mynas were engraved in the collective memories of thousands of children spread all across the tiny valley, in various capacities, coloured with numerous memories. And the progeny that followed who missed his presence went on to inherit the memories of their parents and thus Raja Babu became immortalised as a folk hero, or almost.

Summers and short-lived winters passed by and gradually the antics of the belunwalla began losing its charm and gradually, unbeknownst to us he faded from our memories. Pulled down by the rigours of everydayness and in growing up in general we stopped waiting for his sudden visits, his songs of hinterland and amusing antics. We dragged ourselves in endless useless pursuits – the adages of growing up as an inured youth. Time revved up and I became engrossed in more satisfying passions like reading. Being brought up by working parents has its rewards. For example, you start valuing solitude and develop habits which end up being there with you forever and which you grow up to cherish, solitary pursuits – reading and writing and watching films endlessly – and brooding become part of the routine.

And we grew older.

In the darkest alley of our no-more-nascent imagination, if it was more prodded one could have managed to find the remnants of left glory still untouched and glimmering with some futile hope that it will be brought to forefront not too far away. But we whiled away.

2000s.

Oi daat fokla buri, koraie bhajiya khai muri, aare baap re baap!9

I remember that one random day perhaps a decade since I last saw the Belunwalla, I glimpsed an old shadow humming a familiar tune and carrying colourful wares. For a fraction of a second that old glimmer of childhood nostalgia had almost taken its grip but how adept we had become in feigning maturity. I waited. I was quiescent. I wanted to see him perhaps once more; to see if he was affected by the vicissitudes of ordinary life. He was human too. I thought our paths will cross this time around. I thought I would try to ascertain his age, how cruel time has been on him. But he escaped, disappearing into some other sub-lane to enchant a new generation, becoming oblivious of the others.

I never mentioned this to anyone. I never wanted to make this appear that important at all. It was not, I had so well assured myself.

A few years later I met a man, my contemporary, in a rather ‘hyperlinked cinema’ fashion (this goes for another story perhaps, another memory). He was also haunted by memories but perhaps more by nostalgia. Both of us united by the place we both grew up in or in his case, adopted, got to talk about various things common to both of us, and in trying to build a bridge with longing, we inadvertently ended up finding a common thread in the story of the belunwalla. Both of us recalled our own experiences and image of that ageless, mysterious man who only happened to surface in our memories as a ghost. It was then I noticed how the old man was perhaps a different entity to different children all across our town. The man said. “I always thought then that Daat Bhanga Bura was a secret agent donning his undercover role in this part of the country spying for the government.” I laughed off his witty imaginary tale. He retorted, “I am serious, you know. Why was he travelling all across the region? How was he surviving? What was his sustenance – selling colourful balloons for a couple of rupees? Did you not notice his glittering watch?” I presumed his thoughts then were affected more by the reading of James Hadley Chase than by actualities. I intended to keep those unanswered questions undefiled. For a moment I believed that the balloon piper ignited our innermost imaginations to help us create him. I sometimes wondered was he even a real person or was he the result of hyper imagination fed by collective consciousness?

For Neela, the belunwalla was a magician in disguise. He was purveyor of happiness to forlorn children who were habituated to feel sad, were born sad as many liked to talk about them. She tells me about her memory of the wizened old man. “You know I was in Kindergarten then when I first saw him. The initial reaction was fear but his whistling, his colourful balloon animals were able to unshackle me of the fear and its accompaniments. The moment I came closer he continued his song but changed the expressions this time. “Daat bhanga buri,” he remarked. But instead of getting angry, because this was my default reaction whenever anyone mentioned my poka khawa daat1010, I laughed. It was strange. It should not have happened. But it did. If you ask me now, I cannot explain to you the significance but I guess you do understand it.” I gently nodded. I knew what she meant by being unable to explain the significance. This was the only instance she remembered that she shared with the belunwalla. He appeared later too but this was the event to talk about. By then he turned ordinary. His magic had served its purpose. It was no longer the crutch she needed.

The belunwalla was an indicator of our power of imagination and perhaps unrealised poetry at a nascent level and our understanding of symbols. The fact that a remarkable number of youth or almost middle-aged people still were affected by the fading voice of a mythical man and which made them confess online that his recorded voice was enough to break them down to tears mean that there has to be something quite impactful for this to happen. This cannot be just accidental or coincidental for people en masse.

While trying to form the person called Raja Babu, by excavating moss-ridden memories and through an ethnographic journey of the Internet the one interesting fact that emerges is that he was a mighty good communicator. With every mention of his name how easily one could conjure up his whistles and his expressions. How he managed to enthral an entire generation of children at various points in time still remains a mystery but I believe if we all try to go back and recreate that one moment which we shared with him, we would be able to recall a distinct point in time. A time when we were pure – in thought and in experience.

I was possessed by a very uncomfortable silence within when while going through chronicling of the memories in the Internet I discovered that the Mythical Bird of Bhubon Pahar had passed away in the year 2009. As in life, so in death, our beloved belunwalla departed in undocumented incertitude. I could not find out any verifiable information regarding his death apart from a sketchy newspaper feature and random comments in forums. I realised that we would never be able to comprehend the loss that his invisible death had resulted in. For generations growing up after that period, many things have changed. Childhood has never been the same and will never be the same. It is as if the mythical bird at dusk had flown away with some of the secrets to childhood enchantment.

*

Illustration: Jahnavi Visser

*

Footnotes:

1 Rough translation: “Oh little prince, come here soon, come here, little one.”

2 Balloon seller

3 Toothless old man

4 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nBDbxoO0AT8

5 The Myna from the Bhuban Hills, it doesn’t sing…

6 Aunt

7 Fence

8 The legends talk of a child-snatcher who whisks children away forever in his burlap sack.

9 That rotten-toothed miss, wok-fried puffed rice she eats, Good Heavens!

10 Rotten teeth

1 thought on “The Mythical Bird Of The Bhubon Hills”