Kuntala Sengupta

Wants to know your story, over an orange ice-candy. Or, while she doodles.

Naina looked out of the local train window, the stark sun had begun to set and the people were out of their homes in flocks. Nothing interested her — the outstretched sameness of the lush greens set against puddles of litter, the huts along the tracks with dingy clothes left to dry on the borrowed stones, the women fetching lice on each other’s heads in a line, men playing cards in their bare bodies and skimpy towels, children playing with other children, and young men reclining on their bikes and exchanging the day’s dealings of pride, which possibly could include a couple of blows, or a rape here and a brawl there. Or, of when they would make it big in the city, as promised by their immediate employers. Some young girls looked into yellowed pages of hand-down books, while others looked at the trains, longingly, with dead dreams in their eyes.

Naina looked out of the local train window, the stark sun had begun to set and the people were out of their homes in flocks. Nothing interested her — the outstretched sameness of the lush greens set against puddles of litter, the huts along the tracks with dingy clothes left to dry on the borrowed stones, the women fetching lice on each other’s heads in a line, men playing cards in their bare bodies and skimpy towels, children playing with other children, and young men reclining on their bikes and exchanging the day’s dealings of pride, which possibly could include a couple of blows, or a rape here and a brawl there. Or, of when they would make it big in the city, as promised by their immediate employers. Some young girls looked into yellowed pages of hand-down books, while others looked at the trains, longingly, with dead dreams in their eyes.

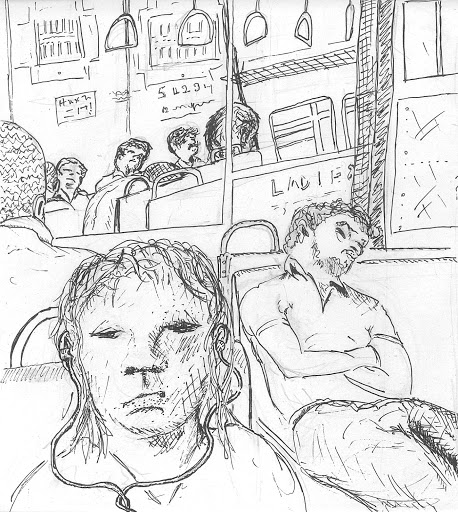

This was a customary noticing of things, as they were, everyday, when Naina returned from her college in the uptown suburb. It never seemed unnatural that the train flashed past by each sight in under a second. She was gifted with the pleasure of timing, and could unfold an incident belonging to another in as quick as a whiff. She seemed distanced today, indifferent. She returned to the tracks after a span of having changed tracks. The familiarity annoyed her and the earphones could not shut out the impossible overpowering of the sense of waste that the cosmetic settlement brought along.

Nine months. What did it most signify, this phrase ‘nine months’? A time-lapse of turbulent growth, perhaps? Of self-discovery and travels within. What did it result in, the ‘nine months’? A life, and a lifetime of tailored nurturing. Naina wasn’t pregnant, but she felt so. Pregnant with ideas and a ruthless need to give birth to all of them in a creative impetus. She looked out of the train window, and tired out of the celebrated poverty and settled her sight inside the compartment to look for the man selling cheap packets of digestive lozenges. She couldn’t digest the fact that her PF-cheque came so quick and easy. Restless, she went back to her deepest within, and traced the route the lozenge would take to find its way to her stomach. She was undergoing a rough patch of wishing to tell, and not being able to. She shunned alcohol and the rationality of senses did not help either.

Her thoughts were punctuated by the approaching station. As would happen in a movie, the little girl, not so little any more got up with her school bag, which would hardly close with books spilling out, and smelling of municipal classrooms. Naina always gave her whatever was at her hand, whenever they met. Someday it would be a slice of guava, other days it would be the spiced puffed rice. She even passed on spare notebooks and half-finished ball point pens, without ever knowing that she would come in that day. And when she had resigned, she did not get to share it with her either.

“Didi!” screamed the girl on seeing her. They had never spoken a word before this. As they spoke for the first time, they spoke like age-old maids, who exchanged pickle recipes over evenings of pushing off hoards of mosquitoes over their heads. And with the suddenness of remembering chores, the maids parted ways into their respective homes. Naina was still in the train. Very pregnant.

Nine months had rolled out, without the promise of a new life. Old stories however, always returned.

*

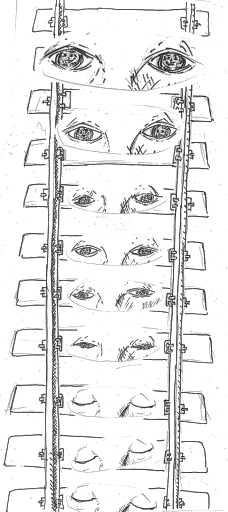

Illustration: Vijay Ravikumar

1 thought on “Train Tales”