Gargi Sengupta

Just another dreamer stumbling through the nooks and alleys of life. Somewhat of an oxymoron in flesh and blood. Sees writing as a way to express opinions and views which gets lost in translation otherwise.

“Aisha Bhatia has the standard chick-lit accouterments – a slightly boring job with a boss who makes her life difficult just because he can. She’s got a coterie of friends – one single woman, one ‘getting a divorce’ woman and a Gay couple, a mother who nags Aisha about her dwindling marriage prospects. She and her friends go out to meet and mingle in the Delhi night spots. Aisha is perpetually almost broke due to spending sprees and enjoys a glass of wine whenever it’s offered.

She meets a cute guy under embarrassing circumstances. Thinks he’s out of her league and snotty. Gossips about him with her friends. Manages a few more prat filled encounters with him all the while starting to fall for him. Then, when she thinks all is lost, manages to hook her man.”

That is a rather succinct summary of Almost Single by Advaita Kala. It is one of the most popular books in the chick-lit genre along with The Zoya Factor. Chick-lits are a sub-genre of the young adult fiction, popularized by the likes of Chetan Bhagat. Indian chick-lits usually have a single, young, independent girl in a big city, looking for answers to the complexities of life and love. Bending the ‘Bharatia Nari’ stereotype is also a major plot device in these books. The Bharatia Nari does not date, drink or smoke. She dresses demurely and accepts the man her parents have chosen for her and she’s happy being the stay-at-home wife and Mother. The chick-lit heroine is an anti-thesis to this stereotype. She socializes at pubs, dates her colleagues and male friends, wears Vero Moda and Levi’s and might as well not marry if she does not find the ‘right guy’. However, commercial success – particularly in the literary and cinematic circles – often comes at the cost of ‘critical failure’. No different story here.

Personally, I am not a great fan of chick-lits. In fact, I feel, they are a rather superfluous way of portraying the ‘emancipated modern Indian woman’. But their “charm” lies in portraying the myriad hues and colours of life of a working city girl with a subtle blend of realism and surrealism. In spite of my many reservations, I cannot help but admire the way they serve as an inspiration to thousands of young girls who have made Delhi, Mumbai or even Hyderabad and Bangalore their ‘adopted city’.

There’s always a tinge of condescension – or worse still open criticism – when one talks of chick-lits in intellectual circles. Yet the sharp wit and omnipresent feeling of déjà vu – particularly for 20 somethings- is undeniable. Aisha’s introduction to the brand of wine called Sula, is something quite a few of us would relate to. It is not every day that you get to taste the best liquor with your initial salary! Besides, a smart, independent, young female protagonist with rosy dreams and fashionable clothes is not too fictitious a character these days. Every second girl you look at in the metro could well be a chick-lit heroine.

Chick-lits loosely embody ‘feminist ideals’ for the lay person: career over marriage and sexual freedom. By default every Indian girl is supposed to be chaste till she weds. Not so with the sassy and freedom loving heroine in the chick-lits. She is pretty much in control of her sexuality/love life and she is financially independent. She does not guard her virginity till she’s married. Neither does she treat drinking or smoking as ‘maha paap’ (super-sin).

But those are not the only ideals espoused in chick-lits. If I look at it in a holistic way, the books explore an age-old adage in a practico-romantic set up: the average woman’s search for Mr. Right while struggling to keep her independence. Reality hardly guarantees the men of our dreams would accept us exactly the way we are. But a story can always have the perfect ending and that’s some solace to all those starry-eyed young maidens.

“Women read such books to ‘escape’ reality. So while it must imitate life to the extent they can relate to it, it must also be a fantasy into a different world of romance. So you need women to be smart, independent and all that, but the hero must sweep them off their feet. I think secretly even independent women dream of a dream lover who will understand and respect them while still being handy around them.”

That’s what an avid reader of romance and a media professional had to say about the chick-lit phenomenon.

Pretty much says it all. There’s this saying about ‘living the many lives that you cannot live through the stories you write (and read)’; rings quite true for both writers and readers of chick-lits.

The sassy ladies in the stories are rather glamorous, be it the way they dress, the jobs they do, the friends they have and even their leisurely activities. Like it or not, glamour has its takers. Increasingly consumerist lifestyles and choices have upped the ante of glamour quotient like never before. Chick-lits capitalize on the trend and it works more often than not. Who am I to judge but?

I cannot judge because concepts like consumerism, glamour or even what one considers being ‘simple’ or ‘dolled up’ are subjective matters. What is consumerism to me might be the ‘normal way of life’ to another and vice-versa. What I consider glamour, could be absolutely bland and boring for another. So I cannot take the liberty to give definitive statements. I can only so much as give my opinion and the reasons behind them. I find the activities of the chick-lit heroine to be more about ‘image’ and a ‘certain kind of lifestyle’ rather than that of self- esteem or self-worth.

“Okay, here goes: twenty-something, single, female, writer, with large groups of friends and who goes out for drinks pretty regularly. That’s my life and that’s what I write about. Okay? Okay.”

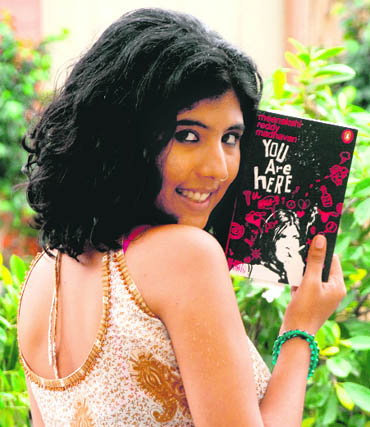

This was the About Me column of Meenakshi Reddy Madhavan’s anonymous blog which she wrote by the name of ‘eM’ (Me spelled backwards and it is also the phonetic equivalent of her initial M). Later her identity came out in the open and eM aka Meenakshi went on to become a chick-lit writer with three books to her name till date.

Interestingly enough, after that ‘outrageous’ introduction, the then anonymous writer also added the following lines:

“The Internet tells many tales and if my identity is revealed, I will age unmarried.”

As I see it, no matter how hard the chick-lit heroines or the ones who write/read about them try to come across as ‘give a damn’ or ‘devil may care’ women, they all have one deep-rooted fear entrenched in their very psyche: fear of being judged and be branded as a slut, a fallen woman, wasted etc.

“If she were a true feminist, she would not need him to define her” is what Reddy Madhavan had to say about Arshi’s (the protagonist in You are Here) tendency to feed on men for her emotional and financial needs. In the same interview with The New York Times, she also added that her characters reflected the ‘dualities that Indian women straddle’.

Effectively then, both the writer and the reader know that they are chasing some sort of a decadent yet intoxicating getaway! It’s easy to say that Reddy Madhavan’s characters do nothing more than pay lip service to Women’s Lib in India. But then, is that not the whole point?

Reddy Madhavan’s heroines live a life and an ideal that might not gain them happiness or contentment in the end, but they are living in the moment. All those acts of rebellion and breaking tradition, do give them a sense of emancipation. Honestly, time and again, even I’ve wished for things that You are Here is about! However, to be fair to the writer, her books seldom end on a fairy tale note. Arshi perhaps is as dazed, lost and confused by the time You are Here ends, as she was when it began. But then, how many girls would actually dare to be like that? Devoid of pre-decided moral obligations and what a ‘good Indian girl ought to be like’. Not many I suppose, and that’s why her books are so intoxicating. They break all ‘taboo’.

Not many writers touch upon the complexities of ‘modern relations’. This is where Meera Srikant sets herself apart with her short novel Chasing Her Shadows. Shorn of atmospherics and finer details, her novel focuses solely on interpersonal relations. It is enough for the reader to know that the characters are eating. There’s no elaborate description, no fancy restaurant or coffee shop to take attention away from the characters.

Shyamala, the protagonist is emotionally contrite. She marries Ravi after he pursues her consistently. Complications arise when Shyamala cannot get over her unfulfilled attractions for a former colleague who keeps coming in and out of her life. Ravi, on the other hand, struggles to find a balance in his relations with other women (an ex and a friend).

While Shyamala cannot get over her unrequited love, Ravi seems too embroiled in his own self to see where he’s going wrong. How the two, snub out their differences and start all over again, forms the crux of the story.

Srikant also brings out certain characteristics of the stereotypical Indian society (maybe not intentionally). When Shyamala muses inwardly ‘the husband can have as many relations he wants prior to marriage but I cannot even have one boyfriend’, it subtly brings out the still patriarchal societal set-up. With all their libertine views and opinions, men still expect a woman to give in to her husband alone. She cannot have any emotional vulnerabilities, let alone physical attractions.

Chick-lit writers do not paint the men as utter chauvinists. Yet, the heroes in the books are the archetypical Indian men. The women do not seem to mind their latent (or blatant) chauvinism. They are almost reconciled to the fact that they will be the second-in-command in all respects. The freedom and the ‘notoriety’ go for a toss when the heroine meets the suave, well-spoken gent with a handsome bank balance. In the end, the books re-enforce the ‘marry a rich guy and settle down for good’ notion. None of the heroines end up with a struggling artist or a regular middle-class guy with big dreams. I find it rather convenient that after being somewhat of a Bohemian, you should settle down with a rich and sophisticated fellow and also have the luxury of having him as your ‘true love’.

Madhuri Banerjee has a different take on ‘true love’ in her book Losing My Virginity and Other Dumb Ideas.

“Kaveri, a prim-and-proper intellectual, is 29-going-on-30 but hasn’t ever kissed, leave alone lose her virginity. Tired of her non-existent love life, with the help of her feisty friend Aditi, Kaveri begins her search for her “Great True Love”. He does come, after a slew of failed dates, in the form of the Adonis-like Arjun. The euphoria of their whirlwind romance doesn’t last long when Kaveri learns that Arjun is a married man. The book traces Kaveri’s journey thence that takes her from being a translator to even making an appearance in a reality show. Eventually, she finds herself (true love).”

The last bit is escapist but not entirely unreal and most importantly very relatable. Being part of a ‘reality show’ is ‘something’. It does give you an identity. And chick-lits are an exercise in finding one’s identity. If there’s a tangible way to do it, well why not?

These books do take a ‘slice out of life’ and may or may not have a happy ending. But what matters is the fact that they talk about women leading a certain kind of life at a specific point in their lives and not all of it is fanciful. Maybe, chick-lits really are not as nonsensical or as shallow, as we would like ourselves to believe.

And if you are still the skeptic, go pick up Arundhuti Roy or Kiran Desai to whet your intellectual appetite!

1 thought on “Literature Of The Chick, By The Chick, For The Chick?”