Sarbajaya Bhattacharya

Sarbajaya is a part time everything.

“Oh rascal children of Gaza./You who constantly disturbed me with/your screams under my window. You/who filled every morning with rush/and chaos. You who broke my vase/and stole the lonely flower on my/balcony. Come back, and scream as/you want and break all the vases./Steal all the flowers./Come back…just come back…”

– Khaled Juma

In India occupied Kashmir, the Army is using pellet guns on civilians. The guns are being aimed deliberately at the eyes, with the perfect shot causing blindness. That is the price the Kashmiri pays for allegedly throwing a stone at an Indian Army tank, or a battalion of soldiers backed by the power of the gun they carry and the law that allows them to wield it at will. A stone picked up from the streets on the spur of the moment appears more dangerous than the barrel of the gun or the wheels of a tank, for it is a stone picked up by a Kashmiri, and in the Kashmiri’s hand the stone is a weapon far more dangerous than any AK-47 or state of the art war machines. In the Kashmiri’s hand, the stone is a symbol of defiance, a symbol of the fight for freedom.

Somewhere towards the end of JANAM (Jana Natya Manch, India) and The Freedom Theatre‘s (Palestine) joint production Hamesha Samida, roughly translated as ‘Forever Steadfast’, a puppet shaped like a human, rises, takes its first steps, and hurls a stone at an Israeli tank. In the hand of the Palestinian, the stone becomes a weapon far more dangerous than the Israeli tank at which it is aimed, more dangerous than the drones circling overhead. In the Palestinian’s hand, the stone is a symbol of defiance, a symbol of the fight for freedom.

The Palestinian’s fight for freedom found a more definite shape with the beginning of the First ‘Intifada’ in 1987. Intifada, derived from the Arabic word ‘nafada’ meaning ‘to shake off’, is usually used to describe the Palestinian struggle for freedom, their fight to “shake off” the Israeli occupation. The First Intifada is said to have lasted for four years, from 1987 to the Madrid Conference of 1991. The history of the Occupation, of course, dates further back. As early as 1948, Palestinians were being driven out of their homes. They were not given the status of refugees by Israel, because to ascribe them such status would be an acknowledgement of Palestine as their country–a country to which they had a right to return. Palestinians who had not left the country, but had moved to another village, to what they thought was a temporary arrangement, were denied the right to return. The idea of homelessness, of seeking refuge in a place away from the one known as home is intrinsically linked to the idea of the longing to return. Israel took away the right, but they could not hamper this longing.

The flame of longing finally grew into a fire with the First Intifada in 1987. Israel employed some 80,000 soldiers to crush the uprising. 80,000 trained, armed soldiers stood in the way of a people who only wanted to sleep in their own home without the fear of bombs and tear gas shells. At the initial stages of the conflict, the soldiers fired upon the protesters. But the rising number of deaths of children and women made them change their tactics. After all, it was only twenty years before these events unfolded that they had claimed their Occupation of Palestine to be the most benevolent one in history. In order to live up to these words, they replaced the bullets with batons, and clubs, and pellet guns. They wounded, but did not kill. According to Save the Children, close to 7% of the Palestinian population under the age of 18 had suffered injuries caused by beating/shooting/tear gas in the first couple of years of the First Intifada. The Madrid Conference of 1991 attempted to revive peace talks between Israel and Palestine. It signified the end of the First Intifada, but the peace talks never came to fruition. Nine years later, in the first year of the new millennium, the Second Intifada had begun. It lasted another five years until it could no longer stand up to the forces of Israeli Defence. Many are of the opinion that a Third Intifada has been in motion since 2014.

The struggle for freedom is not limited to unequal confrontations. Let us, for the sake of history, turn to the freedom struggle in India. For the most part, it had nothing to do with confrontation at all. The struggle for freedom manifested itself in literature (both ‘popular’ and ‘mainstream’), in songs, in poetry, in art. Closer to our own times, even as the Indian State cuts off almost all avenues of communications with the Kashmir valley, the latter speaks to us. Their words come to us in the form of poetry, as snatches of song, as slogans raised in the face of imminent death. In Palestine, the first Intifada, which was initially supposed to be non-violent in nature anyway, was not (despite what the Israeli Defence Force or the IDF would have us believe) restricted to stones, bullets, pellets, and tear gas shells. It was probably Brecht who had famously asked, “Will there be singing in the dark times?” and then proceeded to answer, ” Yes, there will be singing about the dark times”. The Palestine struggle for freedom had also manifested itself through Art.

In Palestine, one of the places where one could sing about the dark times in times of darkness was the Stone Theatre, set up by Arna Mer Khamis with the money she received from the Right to Livelihood award. Arna and her son Juliano both believed in the power of art as a tool for learning and a tool for fighting the oppressor.

But who was Arna? Born into a Jewish family in Palestine, Arna Mer Khamis dedicated her life to the cause of the Palestinian fight for freedom. She worked relentlessly with children in refugee camps, started a project to help them deal with the trauma that was the fallout of the Israeli Occupation. In this project, and at the Stone Theatre, great importance was given to learning, and very often, learning through art. According to Arna,

“The Intifada, for us and for our children, is a struggle for freedom. We call our children project Learning and Freedom. These are not just words. They are the basis of our struggle. There is no freedom without knowledge. There is no peace without freedom. Peace and freedom are bound together. Bound together!”

The Stone Theatre was destroyed in 2002 in an Israeli invasion of the refugee camp.

In 2006, Arna’s son Juliano Mer Khamis co-founded The Freedom Theatre in Jenin. This is what he had to say about The Freedom Theatre,

“…We are joining, by all means, the struggle for liberation of the Palestinian people, which is our liberation struggle…We’re not healers. We’re not good Christians. We are freedom fighters.”

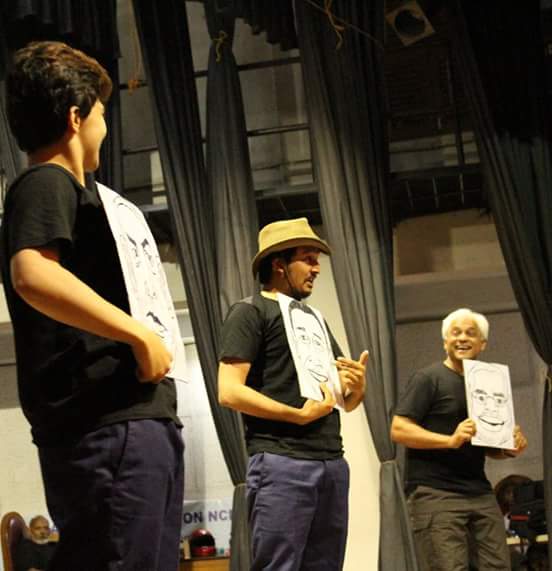

His words echoed in the auditorium of Jadavpur University, in the voice of Faisal Abu Alhayjaa of The Freedom Theatre, and Sudhanva Deshpande of JANAM, right before they began the performance of their joint production Hamesha Samida. Both Deshpande and Faisal stressed on the importance of art as a possible catalyst for social change. They also spoke of the way in which the Palestinian freedom fighter is often labelled as a terrorist. In fact, writes Raja Shehade, the Israeli had initially used the term ‘mukharebeen’ to denote the Palestinian resisting the Occupation. ‘Mukhabereen’ is Arabic for what one would call a naughty child. But soon, the image of the child, the ‘rascal child’, gave way to the image of the ‘irhabyeen’ or ‘terrorist’. In a world where the argument “All Muslims are not terrorists but all terrorists are Muslim” seems to find a considerable number of takers, such easy equations involving the protester and terrorism comes as no surprise. The Freedom Theatre wants to project a different image. They came before the audience, not as terrorists, not as art practitioners, but as freedom fighters, an identity they held close to their hearts.

At Jadavpur University, Kolkata, the play was performed inside an auditorium, which perhaps took something away for the performance, because it had been designed as a street play, a form that both JANAM and The Freedom Theatre have mastered over the years. JANAM, of course, is famous today for its street theatre, although they have performed plays designed for the proscenium. Their founder-member, Safdar Hashmi was fatally injured in an attack that the members of JANAM suffered while performing one of their best known plays Halla Bol while they were performing in Jhandapur in Shahibad. Hashmi passed away in a hospital in New Delhi. This was in 1989, eleven years after the formation of JANAM.

Twenty two years later, 4000 kilometres away, Juliano Mer Khamis, the founder member of The Freedom Theatre and the then convener of the group was murdered by persons unknown; an unfortunate tragedy shared by the two groups.

In Delhi, JANAM received the news with deep sadness. They had been in touch with Juliano Mer Khamis and the plans of a joint production were still at a nascent stage. Juliano’s murder brought these plans to a temporary halt. Some years later, the thread of communication was picked up again. Sudhanva Deshpande of JANAM visited Palestine, and saw the group at work. Their exchanges culminated into the Freedom Jatha – a long march for freedom. Hamesha Samida was a part of that march. Between December 2015 and January 2016, the play travelled across several Indian cities including New Delhi, Lucknow, Mumbai, Banglalore, and Kolkata. In each city, they spent an average of two days, going up to four or five in some cases. They performed in several locations in one city. In Kolkata, for instance, they performed at Jadavpur University, and a slum in Rajabajar in the northern part of town. The range of their audience is varied, and it is something they have obviously kept in mind while putting the play together. At the outset, the most difficult hurdle seems to be language, for the play makes copious use of Arabic, the language spoken by all the Palestinian actors. In many of the spaces where they performed, they may not have found an audience well-versed in the language. But the two groups play a clever balancing act. In some instances, the expression of the actor, physical and facial, is enough to convey the message. In other instances, the Arabic dialogue is repeated in Hindi by an actor from India, without making it seem repetitive. In one instance, two women speak at the same time – one in Arabic, and the other in Hindi.

Remaining true to the spirit of taking theatre to the masses, the play is short and not overtly complicated. But neither is it watered down in any way, not once does it undermine or insult the intelligence of the audience. In the crisp running time of twenty five minutes, the play succeeds in capturing the story of Palestine’s struggle for freedom – through song, and dance, and first person account. The story telling takes place in a play within a play, where the director (played by Osama Al Azzeh) frantically searches for an actor named Ibrahim and demands an olive tree and a tank as props that are essential to the performance. But while he continues his search, the play within the play – the story of Palestine, begins to unfold in front of the audience. Using a limited number of props that include a ladder, a puppet, and flags, and under flat lights, the play recounts how Palestinians were and continue to be driven from their homes, the brutal nature of the Israeli Army, and the role that the leadership of Israel, USA, and now India have to play in continuing the Israeli Occupation of Palestine.

They represent Palestine through three symbols – the olive tree, a trunk, and a key. The olive tree, they say, is integral to the lives of all Palestinians. In fact, in the framing play, the director actually equates Palestine with olive trees. Olive tree is equal to Palestine, he says, and Palestine is equal to an olive tree. A play about Palestine, he insists, cannot be performed without an olive tree.

Within the play, the olive tree brings back memories of home, of days spent in its shade, the air heavy with the scent of olives when the trees are in full bloom. The trunk or the ‘sandookh’ is the baggage the Palestinian must carry, both literally and metaphorically, when they are driven from their homes. “One morning, the Israelis attacked our village,” says one of the women in the play, “and we packed our lives into the trunk and were on our way.” An entire life packed into a trunk. A trunk filled with memories of home, and the scent of olive trees. And finally, there is the key. The key to a home to which one can never return. The key is a constant reminder of homelessness, of the scent of olive trees, of a time before the darkness came.

They also sing. They sing in a language that the audience does not understand. And yet, did we not understand? Darkness, perhaps, speaks a universal tongue.

The puppet is one of the most significant props used in the play. It represents Palestine itself, a Palestine that is asked (forced?) to give its land away, a Palestine that is tortured and brutalised, but also a Palestine that fights back, that picks up a stray stone and throws it with all its might at the tank that looms over it, and finally, it is able to drive the tank away. It is fitting that the puppet is shaped like a human being, for what is a country if not the people who inhabit it?

The final song of the play, (sung beautifully by one of the Palestinian actors) begins after the tank has been chased away, and it sings of the end of the dark night and the coming of a new dawn. Perhaps, in that new dawn, the rascal children of Gaza will come back.

*

Notes:

- Pearlman, Wendy. Violence, Non-violence, and the Palestinian National Movement. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Said, Edward. On Palestine. Ed. Vijay Prashad. New Delhi: Left Word, 2014.

- http://www.thefreedomtheatre.org/

- http://www.jananatyamanch.org/

- https://opt.savethechildren.net/

***

Images: Ritaj Gupta

2 thoughts on “The Rascal Children Of Gaza”