Memories of the Spring Thunder

Translation: Souradeep Roy

.

Translator’s Note: I took upon translations of these poems written in prison by Naxalites as a way to understand and process some of my own feelings when several close acquaintances and comrades were imprisoned in the last few years. In my own academic work, I was dealing with the prison. As I was working on the translations in October 2020, I was writing about the Bengali theatre group, Nandikar’s adaptation of Antigone during the Emergency — independent India’s first formal dictatorship — for my dissertation at Jawaharlal Nehru University; I have just finished teaching The Island — set in Robben Island during apartheid South Africa, written by Athol Fugard, John Kani, and Winston Ntshona. — in London as these translations are about to come out.

However, the knowledge of my own freedom in the context of my comrades’ imprisonment was very, very unsettling. I felt that the only way to understand the situation could be by seeing the contemporary moment as one moment in a long historical context of the emergence of the state and its reliance on imprisonment. Poetry offers a way to understand what the condition of imprisonment might mean for someone. This is also why, I think, in the context of a failed revolutionary action, some of the Naxalites took to poetry. My translations were my attempt at actively listening to them. Samir Ray’s poem, “I could not write a May Day poem, Birenda” in particular, I feel, is both an archive of feelings within the prison, but also a corrective to what we think revolutionary poetry might mean.

A revolution is both a triumph and a tragedy. Every successful revolution is a moment of celebration that can only be built on the edifice of failed revolutions from the past. Revolutionary poetry must carry the tragedy of past revolutions as well, as much as it sings of hope. It must acknowledge and contemplate despair as necessary moments in a revolutionary’s life. Samir Ray, in addressing his poem to his Birenda — Birendranath Chattopadhyay, a Marxist poet — is making this claim. He writes of his inability to write a “May day poem,” a typical poem of hope perhaps, through another kind of poem. This poem encapsulated my own despondency in my late twenties, a strange sense of fatigue, a sense of giving up, leaving my own country. When the new government had come to power in my early twenties, I too could have perhaps written a May Day poem, but like Samir Ray, even though my situation is not remotely close to his, I cannot write one in my late twenties.

.

I Couldn’t write a May Day poem, Birenda

By Samir Ray, written in Presidency Jail

Birenda, I am not beyond forgiveness

so do forgive me for this.

When all of you were writing poems after taking out — not seven, not five —

but an entire sea of red flags in ten thousand hands in the city of Kolkata

I was here, here in Kolkata Presidency Jail.

Not having found any grace in the moon,

I caress my mother’s face with empty hands in the end;

my mother is unwell, temperature on her sick skin,

I couldn’t write a May Day poem Birenda.

I can’t sleep at night

I lie awake

and listen to the twenty year old Asheem on my right

fed up after calling on his mother again and again

He hasn’t seen his mother from this side of the jail for a long time —

on my left is Raghunath Bir Pradhan, he has a good physique

It seems a young Greek man is becoming a stone with each passing day

His father passed away after he came to this jail

His mother has been bed-ridden ever since, they have only one sister. Their family has been destroyed;

yet I have never seen a tear-drop in Bir’s eyes

There are no tears in eyes made of stone I suppose!

But this stone laughs, talks

It has enough red and white blood

to smile

to speak —

yet censored and passed — his mother’s letter arrives

What kind of stone is this, a stone which melts

Whenever I look at Bir’s eyes

I can see my mother’s teardrops

It seems as if the fruits from grapes fall as drops of tears

This is why I can’t sleep, I listen to

the periodic gongs of the central sentry tower’s bell

and reach out for my mother’s eyes with my hands.

Please sleep, sleep my dear mother

I am sitting here beside you like an obedient child —

but what do I do, tell me

my mother won’t sleep

she won’t get herself a cup of water even when she’s dying of thirst.

I couldn’t write a May Day poem Birenda!

Arun, a little far from my left,

wearing a red gamcha, is restless

God has given him a pass to spend all his life in a jail —

he had stepped out of his house such a long time ago determined not to make any mistakes

His mother had said, “I send my blessings to you, my son,

return like a winner”

Arun hasn’t returned to his mother,

he has spent six years inside a jail surrounded by the sentry-box,

when he had reached the shore of the river

tired, quite tired after swimming through the waves,

facing the ripples of his mistakes for six years,

his younger brother had passed away

His father came with the news, “You mother wants to see you

she hasn’t been able to get up from the bed”

Parole petition, his father’s telegram,

everything like instances from Saratbabu’s novel Obhagir Sorgojatra[1]

the spires of the smoke mixes into some place I can’t find!

Arun couldn’t meet his mother eventually

With a gamcha wrapped around his head Arun is restless

After some time he will get up, light a bidi, and sing a song

Or else he will draw out a book by Lenin.

His eyes light up in the summer

as if to shame summer itself.

I couldn’t write a May Day poem, Birenda.

On my right, around fifty yards away is Yasin Mollah

He had lost his mother many, many years ago, in his youth

He has been homeless since then

He is built like the strange shapes of dispersed clouds —

he knows anything there is to know about any of the machine parts

yet, for some reason, he couldn’t braid his life

with the rhythm of machines and the songs of life —

Yasin, whom the struggles of life have shredded him into many pieces,

couldn’t find his mother in machines, in life

This is why this startled young man Yasin has lived his life in the sun…

The same Yasin received a letter from his mother after twenty years;

I have only seen him shake

not using any analogy metaphor here

Yasin is just shaking with his mother’s letter on his hands

here, right in front of me —

Yasin’s mother was supposed to come on Monday

she had come too

But even after twenty years Kunti had not received a letter permitting her to enter Birenda

Yasin’s mother couldn’t cross the challenge gate and see her son

She glanced at her son’s face, towards the sentry

Then she walked away, she was walking away, Yasin’s mother, my mother.

I couldn’t after all write a May Day poem Birenda!

In one of the four wards away from ours

Robi is writing a poem lying down

Irritation — perhaps pain and disillusionment too — in the chest, drunk river in the monsoon

races ahead of metre —

don’t look for symmetry in the metre in the waves

It is coming towards you after tearing the mask off his face

with a terrible irritation in its chest —

Robi holds the pen and paper, sits up with the blood

on his hands;

Remember Akashvani’s jol pore pata nore — all kinds of

such simple news —

“Youth dead after clash with the police” —

a brother’s corpse floats on the Ajoy river.

When God was playing polo with equality-fraternity-freedom

in the parliament in Delhi

there were three bullets in my brother’s forehead, chest, stomach

as if he is surrounded by sohag chand bodoni girl, lovely…

Robi gets up

Robi walks through the four wards fiercely

His mother’s face in the interrogation chamber

She had started so early in the morning

After looking for her son in two zillas, ten jails her face now

in front of the interrogation chamber…

O dear, they won’t allow her hands, her chest to hold her little boy

even once,

God won’t allow her to hide!

The mad mare falls on her chest as she tries to hold back her tears

Rush of blood flows out of her mouth, out of the mother’s mouth

Your blood is so red, dear mother,

that a nation of palash and silk cotton

feels ashamed!

Robi’s mother has descended the stairs of the interrogation chamber

She has descended the stairs

She has smeared the blood from her heart on her face and descended the stairs…

“Ekbar kol khali hole mayer mukh bhore na go bhore na”

I do not believe, I do not believe, I will not believe

in this rural proverb, my dear mother.

Mother, please go to sleep, I am sitting here next to you

like an obedient child.

I have still not found any grace in the moon

That’s why I caress my empty hands on your face in the end…

Sleep, dear mother, please go off to sleep

If you get up when the dawn falls, allow me to take leave.

Robi’s mother descends the stairs of the interrogation chamber here

right now, in front of my eyes

Robi’s mother descends the stairs of the interrogation chamber here

She carries all the blood in her heart as she descends the stairs.

I could not write a May Day poem Birenda.

.

Hazaribagh Jail

After the custodial killing of Prabir Roychoudhury inside Howrah Jail

Shut up

Here sleeps my brother

Don’t call him up with your sullen heart and overcast face

because he is all smiles, he is laughter

Don’t cover his body with flowers

What’s the point of dumping

one bundle

after another?

If you can

entomb him in your heart

You will notice

your sleeping heart is racing

to the calls of the bird that resides in the heart

If you can

shed a few drops of tears

give all the blood in your body

(This poem was inscribed on the walls of the Presidency Jail)

.

[1] This is a reference to Saratchandra Chattopadhyay’s short story, “Obhagir Sorgojatra” (Journey of an Unfortunate Woman)

.

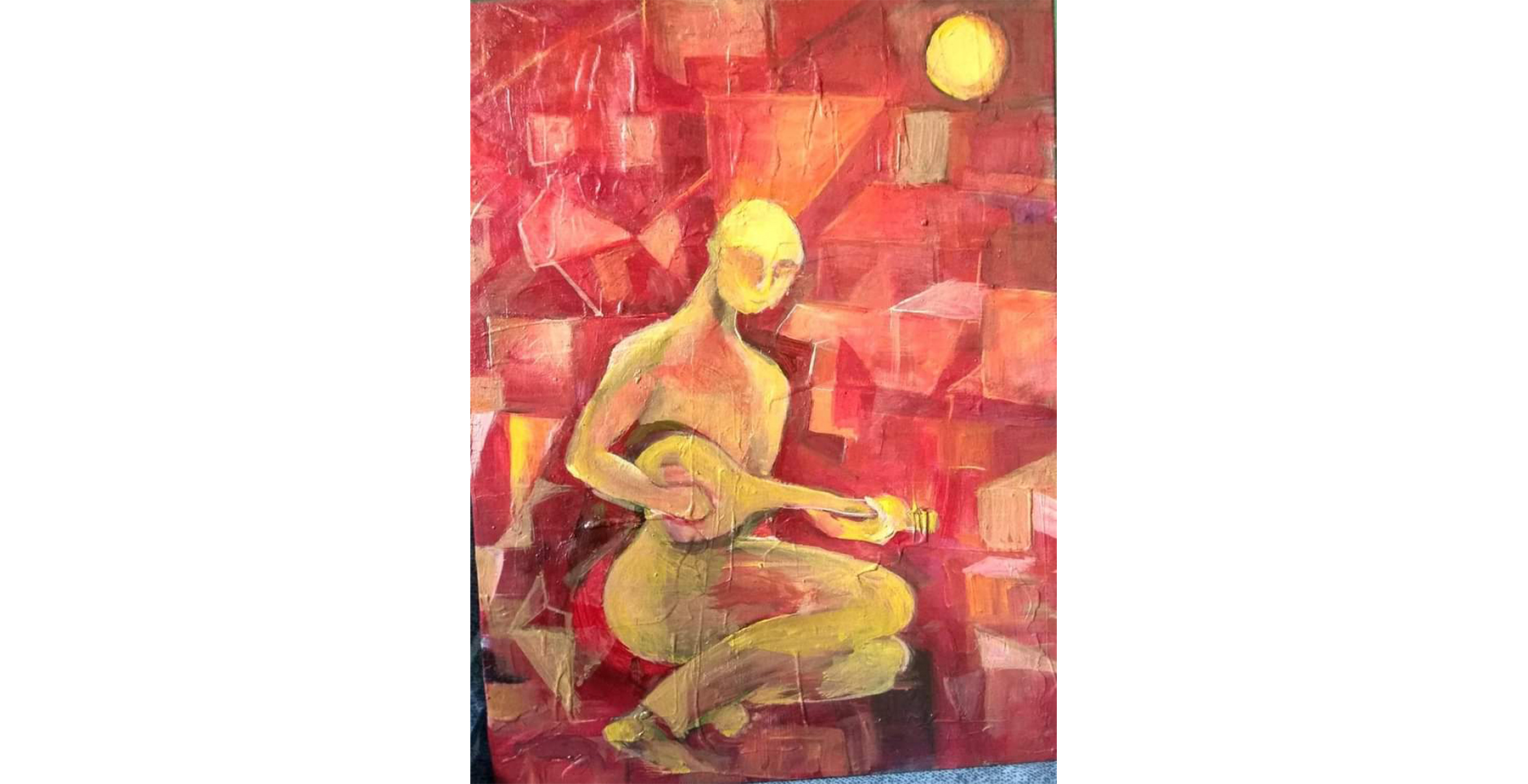

Illustration: Amrita Samanta.

Samir Ray (1938-1994) was born in Faridpur in undivided East Bengal. A member of the editorial collective of the left-progressive literary journal, Nandan, Ray, inspired by the historic event at Naxalbari, joined the movement, and was later imprisoned. An active organizer in many radical-left poetry and cultural initiatives, Ray remained, almost exclusively a poet of the Bengali radical little magazine movement. His first book Staliner Coffinbahokera was published in 1971, followed by Ranapaye Hete Jabo, Paramesh, Borof and Dhormo Phul Porachhe. At the time of his death, Ray was actively associated with the then much-discussed workers’ struggle at Kanoria Jute Mill in Phuleshwar, Howrah.

Souradeep Roy is a poet, translator and performance maker. He is currently working on a PhD on the history of the Bengali theatre movement (primarily the IPTA and the group theatre movement) from the 1940s to the 1970s, and teaching theatre making at Queen Mary, University of London.

1 thought on “”