Aainanagar in conversation with Aniruddhan Vasudevan

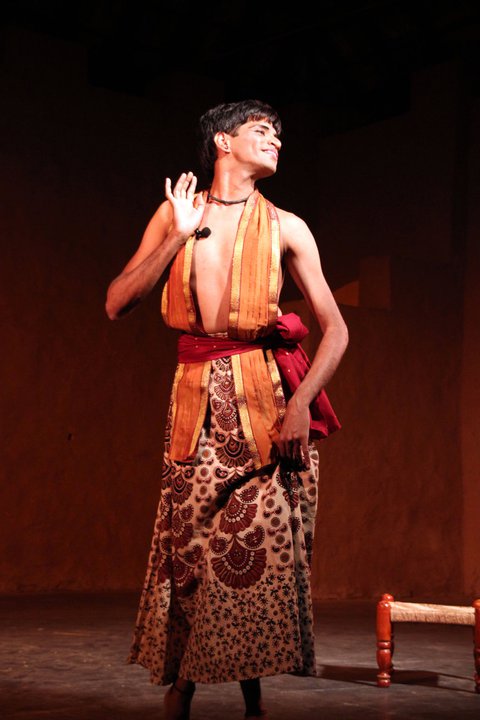

Aniruddhan Vasudevan is an accomplished Bharatanatyam dancer, performer, writer, translator and activist based in Chennai. His dance/theater piece ‘Brihannala’ raises questions about gender in Indian Dance, Theater and society.

Q: Why Brihannala? It’s an Indian mythological character and as a Bharatanatyam dancer you may have sought your protagonist in that literature…there might be other reasons…but I’m naturally assuming that the issue is the so-called social ambiguity of gender. But then there were other characters with – I shouldn’t say similar – may be parallel gender-issues like Shikhandi, Yuvanashva, even Chitrangada in the same literature.

Aniruddhan: The answer to that is, I am afraid, rather simple and straightforward. I started learning Bharatanatyam in 1988 when I was six years old. That was also the year BR Chopra’s famous mega TV series, ‘Mahabharat,’ started airing on Doordarshan. The episodes that had me riveted were the ones where we see the Pandavas in the thirteenth year of their exile, living in disguise in the kingdom of Virata. Arjuna becomes Brihannala, a transgender woman. I was really enthralled by that visual representation of Arjuna’s temporary transformation. That impact, I think, stayed with me. Later, as a queer adult, I have had moments of deep gender crisis, but they were always short-lived, though intense, experiences. And when I looked for some kind of a metaphor or a short-hand or an ideal-type to understand these temporary intensities of gender I experienced, I thought of Brihannala again. Plus, I also had this weird crush on the Arjuna I saw on TV, and I could not tell if it was actually a puppy crush on the actor (Feroz Khan) who played the role). Then later there was also this intense Krishna love, triggered by dance songs and Vaishnava poetry. So all of it seemed to somehow converge on Brihannala as a figure that helped me make some order out of this chaotic flow of desires.

Q: Why the form? I mean you could do a Varnam on Brihannala. But you chose to make it a theater within a theater. I suppose I’m asking you to talk a bit about your dance background as well your theater background here (and you chose one over the other in this case), so that one knows where the form came from.

Aniruddhan: You see, the story was an intensely personal one, with Brihannala just helping me by being a touchstone, a figure aiding me in understanding my own intensities of gender and sexuality. I did not think a traditional Varnam format would work. In fact, I did not calmly consider options. I was writing down a narrative structure and words and I saw it as a piece involving performance and storytelling and poetry. I did not see it in the Varnam format in my head. I mean, the piece has changed since you saw it last, but I still feel the need to speak, recite poetry, make jokes, etc. The loose form I have now helps with all that! There is also that different joy of dancing a full Varnam, which I continue to get from, well, dancing a full Varnam!

Q: I remember having felt that it had a mood of local theater (like Yatra in Bengal or Koodiyattam in Kerala), where the audience was being dragged into an intimate space of the protagonist. Do you think a more intimate space than the proscenium that you used would have worked better? Or did you consciously choose or prefer to be the proscenium performer, keeping the audience at a distance, at the risk of making it a discourse rather than an intimate conversation?

Aniruddhan: It doesn’t work well at all as a proscenium piece, you are right. That is what I felt after the first few shows. The later ones have actually been in intimate settings, with smaller audiences, and no level-separation between the audience and me. That certainly works well. I had not chosen the proscenium earlier. I had just sort of solidified a new piece, and I was getting asked to perform it, and I didn’t really think of questions like, “Oh what sort of venues? What kind of a stage would work?” which I should have!

Q: For that matter, is Brihannala a theater or a dance? You do use some of the Mudras, the dancy walking, even Thattis towards the end with the drums. What are your ideas about the intersection of dance and theater? Is there a sharp line between these two? Is it so that within the format of Classical dance the line is somewhat sharper/faded in comparison to contemporary dance/dance-theater? How has your background of dance-theater affected this choice? What other dance-theaters have you been part of before this?

Aniruddhan: Initially I had some difficulty and self-consciousness in calibrating the degrees to which dance and theatre could mix in what I did. I am a lot less so now, so in the latest version of Brihannala there is a lot of movement. I have no problems at all with the intersection of dance and theater. So many of the Indian forms are composite ones, with dance, theatre, and music foregrounded and calibrated differently at different times. I think it works better to recognize the spark of an idea, work with carefully into a good framework for a performance, and ask what form that idea demands, how do you feel it happening, what do you see when you close your eyes and hear and visualize it?

My training has largely been in Bharatanatyam. In 1988, I started training with Guru Kuttalam M Selvam, a wonderful teacher, in Kumbakonam, my hometown and where I lived till 1999 when I finished my higher secondary. Then I moved to Chennai to learn from Guru Chitra Visweswaran. It was a dream come true. I always wanted to learn from her. My sensibilities were drawn to the more rounded, less staccato, less geometric, more liberated way of moving, which I saw in her work. Of course, I later learned that it was very hard to move so gracefully and flowingly, because it needs a lot of grounding and control. So it was all really enjoyable training. I was also part of the Bhagavata Mela tradition in Melattur for some years, and spending several summers taking on and watching female roles performed by men was also a very significant experience for me. And Bhagavata Mela natakams have dance and theatre, including vachika, the use of spoken language, in Telugu.

Q: Why the need for going out of the Classical? I know for some contemporary performance artists, it’s the urge to go out of the story-telling mode. But you are still telling stories through your performance. So – I think it’s related to my first two questions – is it the character or the performer that required this modern form, and in what ways?

Aniruddhan: I wanted words, and I wanted the words to be spoken by me, you know? Not by an accompanying singer. I had also trained a little in theatre with Dr Rajani at the University of Madras. He was the one who really made me comfortable with acting on stage. He also taught us to enunciate, to hold pauses, etc. So I like to move, I like to tell stories, and I like to act. And the way the idea for Brihannala took shape in my heart and head already had these forms in it. I just went with it.

Q: How has the classical training affected Brihannala? I remember you saying that your Guru was very positive about your own exploration. Did you discuss the process of creating Brihannala with her or any other classical dancer/other friends of yours? Were there suggestions by any of them that you encrypted in your performance? Basically I’m asking you to tell us a bit about the making of Brihannala – in whatever manner it works for you…

Aniruddhan: Oh my teacher, Chitra Visweswaran, was there when I first showed ‘Brihannala’ as a work in progress at the Madras-to-Chennai Local organized by GM Sajani in March 2011. She loved it, and after the performance, right outside the venue at Spaces in Besant Nagar, she stood with me, combing through what worked and what didn’t, and giving me suggestions for improvement. It didn’t surprise me one bit. She has always been incredibly supportive of whatever I do.

I think the training in classical dance I have is the fundamental discipline and grounding I have. I am very grateful for that. The traditional forms of piety and gendered desires expressed in Bharatanatyam don’t always sit well with me. But there is something to those years of training and proximity to texts, music, rhythms, and discipline. Very, very helpful!

Q: This is an experience you may not have faced in Chennai or abroad, but in many states on India, Dancers, especially male dancers are considered to be queers irrespective of how they identify themselves. Was this ‘queerness of the form’ in your conscious thoughts while making Brihannala?

Aniruddhan: Yeah, these flippant remarks about all male dancers being queer are made all the time. There is no sense to that. It is very tiresome to hear that. But we can make it productive by asking what does dance do to the body, what does a dance like Bharatanatyam do to the male body, does it have any effect on the desires and desirability of those bodies, etc. And that line of thinking can be fun to engage in, especially if we dancers do so ourselves!

Q: You have been working for LGBT rights in and out of Chennai for a long time. How has that affected your choice and development of the piece? How was the reception of the piece in and outside Chennai? Were there interactions/ discussions that led you to changing or rethinking of the piece?

Aniruddhan: The work doesn’t directly tie into the question of rights, but it is definitely related to the fact of my being queer. I mean, ‘Brihannala’ doesn’t directly speak about rights and advocacy, though those are important to me. It is about a personal narrative that has possibilities for being relatable to others. The reception has been great! I also get to work with local musicians and artists when I go to present Brihannala, so it also builds relationships! Also, the work itself has become less shrill and angsty, I think, which I sounds like a good thing to me. (I’d say it has something to do with my becoming, in general, less shrill and angsty as I glide into my 30s, but that is a question of opinion!).

I am very much part of the LGBT community and our work in Chennai. My PhD research too is to document, understand, and historicize at least some of that work. Chennai is home, where I hope to return for good soon.

Q: Anything you want to say about your experience regarding the stance of Hindu fundamentalism, which hails Mahabharata as one of its epics, in its dealing with queerness in Art or queerness in general?

Aniruddhan: Yes, it is important for me to be constantly aware of what texts , myths, and ideas I am working with, and the purposes they could serve for others. Not everything can be reclaimed successfully. Not everything needs to be reclaimed either. Even without the issue of Hindu fundamentalists’ appropriation of texts such as the Mahabharata, we’d still have other things to worry about: Brahmanical Hinduism, its views on women, caste, equality, sexuality, etc. I mean, my relationship to texts like the Mahabharata is messy to begin with. I need to recognize that and see what that means and why I want to continue to engage with figures and ideas that come from them. It is an ongoing process. I don’t think I can resolve it once for all.

Q: Personally there was something that I adored in your piece, which is an obvious component of humor, or may be I should say ‘endearing friendly sarcasm’ in the way you asked questions to the audience through the performance. But the matter that you were addressing was neither of endearment nor of humor. Why this choice of style? Is it just being you? In which case I would like to ask you if you felt the need of going out of your own self in some sense through this performance. Because I personally believe, when we are doing a piece which is well within our comfort-zone of being and stylization, it is somewhat easier for the performer to do what s/he is doing. So was there a point of pushing yourself out of your comfort-zone through this piece in any fashion?

Aniruddhan: It is interesting that you ask about comfort zones. In some senses, yes, I was going out of my comfort zones in creating a new work all by myself, which was neither a straightforward monologue nor a traditional dance piece. Besides, it was also going to a different form of ‘outing’ myself. So, yes, I had that feeling of being out of my comfort zones. But in another sense, I have never been in a zone that has felt comfortable for long. Even with Bharatanatyam it has been an ongoing mediation for space and voice. What I mean by that is, my relationship the notions of gender, sexuality, religiosity, etc., that pervade the dance texts is a heavily mediated one. So if I want to continue to engage with Bharatanatyam, I need to constantly think about what poetry, which songs, what is their politics, etc. And then there is the queer sense of always feeling out of place, always feeling I should be elsewhere doing something else. So I have learned not to take comfort for granted and also to value discomfort. It can be very productive.

Humour – I didn’t put it in consciously. But I am told I have a sense of humour, often directed at myself. But there is also a queer history for that kind of humour, I think – to be a jester, an entertainer even in real life situations. In my case, it came out of a desire to be liked and popular, so that one day when people did find out I was queer, they’d overlook it! Self-hate and fear of disclosure turned inside out into humor and sarcasm. And long after the hate and fear are largely gone, I find the humor still useful as a coping mechanism.

Q: Violation of gender rights and societal hypocrisy regarding it have rather been a matter of violence and there have been performances which are more ‘fitting reaction’ to that violence in the way of expression (Vagina Monologues, for example, or Molaga Podi, say). Basically I’m asking if anger is a prominent component in your piece and if yes, then how you dealt with it in the way you expressed your thoughts.

Aniruddhan: Oh Anger certainly has its place in life, politics, and art. Molaga Podi is such a brilliant play, and Srijith has done such a terrific job. It covers a larger canvas, speaks of caste, gender, and larger and entrenched oppressions. Anger is the fitting response to what we see around us. My piece doesn’t even claim to speak of a generalized experience. It was just an attempt to speak about what mythology, its popular representations, my own relationship with my body, my sexuality, my sufferings on account of the silences I have endured and sustained about these have to do with one another. Anger just didn’t have a central place in this particular piece.

Q: Who else were there in the Brihannala team?

Aniruddhan: Oh, I have worked with some wonderful people. Asma in Chennai helped me immensely with shaping the script and overseeing my practice. She also gave me much confidence whenever I wanted to give up. I am very grateful to her for that. My dear friend L Ramki played the Veena for the piece on two occasions. Veteran Mridangist and someone who has worked with my teacher Chitra Visweswaran for decades, Adyar Gopinath, played the Mridangam for this piece many times. Uma Sathyanarayana, my dearest friend and a most talented singer and dancer, has sung for me. When I performed at the Math Science Institute in Chennai, R Thyagarajan, one of the finest flautists I know, played for me. In the US, Padmini Raman, a graduate of Kalakshetra and the grand-daughter of the legendary teacher and nattuvanar, Kamalarani, has performed nattuvangam for me – three years ago at the Queer ‘I’ performance festival in San Francisco and a month ago at Stanford University! Shabi played the tabla when I performed for that performance at the lovely Women’s Building at the Mission in San Francisco. And working with Sterly D., an incredibly gifted percussionist and a wonderfully open and warm human being, at Stanford last month, was particularly memorable.

1 thought on “Brihannala: A Myth, A Journey, A Dance-Conversation”